Languaging: The Strategic Use Of Language To Change Thinking

This is based on the Category Pirates ?☠️ Newsletter.

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and fellow Category Pirate,

Category Design is a game of thinking.

You are responsible for changing the way a reader, customer, consumer, or user “thinks.” And you are successful when you’ve moved their thinking from the old way to the new and different way you are educating them about.

The way you do this is with words.

Which means if you can’t write what you’re thinking, then you aren’t thinking clearly. And if you aren’t thinking clearly, then how are you going to change the way the reader, customer, consumer, or user thinks?

In previous letters, we have written about the different levers you can push and pull to differentiate your business (and even how to differentiate yourself in your career). But how you get customers to understand what makes you different, how you get investors to understand why you’re moving from one profit model to another (like Adobe did), and how you get employees, team members, and fellow executives to align their efforts (aka: align their *thinking*) is by using very specific, very intentional language. (At first blush, it’s hard to be against something called, “The Clean Air Act.” That’s on purpose.)

The strategic use of language to change thinking is called Languaging.

We believe this is one of the most under-discussed, unexamined aspects of business & marketing today.

- When President Biden orders U.S. immigration enforcement agencies to change how they talk about immigrants and change terms like “Illegal Alien” to “Undocumented Noncitizen,” that’s languaging.

- When the dairy industry spends 100 years educating the general public that milk comes from cows, and then someone comes along and introduces “Almond Milk” (or Oat Milk, or Flax Milk), that’s languaging.

- When the whole world understands what an acoustic guitar is, and Les Paul comes along and starts wailing away on an “Electric Guitar,” that’s languaging.

Languaging is about creating distinctions between old and new, same and different.

Legendary Category Designers are Languaging Masters.

A demarcation point in language creates a demarcation point in thinking, creates a demarcation point in action, creates a demarcation point in outcome.

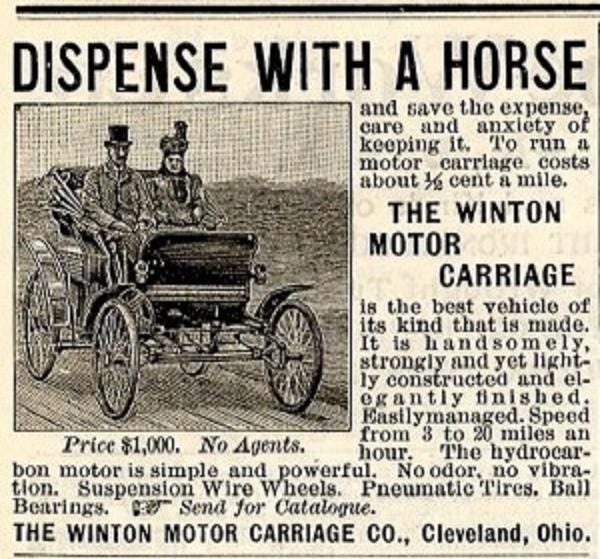

When Henry Ford called the first vehicle a “horseless carriage,” he was using language to get the customer to STOP, listen, and immediately understand the FROM-TO: the way the world was to the new and different way he wanted it to be. Had he called the first vehicle a “faster horse,” that would have been lazy languaging (and lazy thinking).

Sara Blakely insisted that Spanx was not just a “product,” it was an “invention.” Today Britannica lists her as an “American Inventor.” That’s not an accident. It’s the strategic use of language.

And it all starts with your POV.

Your Point Of View Of The Category Is What “Hooks” The Customer

The language you use reflects your Point Of View.

And your Point Of View frames a new problem and a new solution in a provocative way.

If marketing is your ability to evangelize a new category, and branding is how well you can associate your product with the benefits of the category, then languaging is how you market the category, and your brand within that category, based on your company’s unwavering, unquestionably unique point of view.

You can tell when a company doesn’t have a unique POV of their category when their “messages” conflict with one another, have unclarified and “weak” aims, or worst of all, have no clear aim at all. Today they’re evangelizing one category, tomorrow they’re evangelizing a different category (all the while thinking they are “trying out different marketing & messaging phrases”).

For example, a cereal company might run one advertisement saying, “The healthiest way to start the day!” The very next campaign, however, they might change the message to, “A healthy breakfast alternative.” What’s the cereal company’s unwavering POV of the category?

Is it that breakfast is the best way to start the day—and they’re the solution?

Or is it that breakfast isn’t the best way to start the day—and they’re the solution?

Frame it, Name it, and Claim it

Companies with unclarified, undefined POVs eventually come to the conclusion that they have a problem (sales are down). But they end up stating the root of their problem in the way they ask for help: “We need to work on our messaging.” More times than not, what they mean when they say “messaging” isn’t actually messaging—but category point of view.

As a side note, most messaging is meaningless, context free, point of view-less, forgettable garbage. “Experience amazing,” “Imagination at work,” “That’s what I like,” “Run simple,” are taglines for who? Don’t know? Neither does anyone else. Lexus. GE. Pepsi. SAP.

The reason this clarity is so important, and why we want to draw lines in the sand between category point of view, languaging, and messaging, is because improving a company’s messaging in absence of a true north category POV is a (and we use this word very intentionally) “meaningless,” money burning project.

- A POV is, “What do we stand for?”

- Languaging is, “How do we powerfully communicate our POV?”

- And messaging is, “What should we say?”

Well, how can you possibly know what to say unless you know what you stand for? What difference do you make in the world? What problem do you solve?

Your point of view should be well defined and chiseled into the company’s tablets, with intentionally chosen words that reflect the company’s POV, so the true science of messaging can begin: a never-ending experiment of swapping in and out of words, phrases, promotions, testimonials, and other “messages” in order to figure out which are (another very intention word here) resonating and most effectively evangelizing your category POV.

And it all starts with how you choose to Frame, Name, and Claim the problem.

For example, there’s a reason why men have “erectile dysfunction” and not “impotence.”

Impotence has very negative implications attached to the word. If a man says he is impotent, it’s as though he has a character flaw. It means “not manly” or “unable to be a man.” That’s not a word very many men want to be associated with—meaning men don’t want to admit to having such a problem. (Hard to sell a solution to a problem no one wants to admit to having!)

In order to solve this problem, Pfizer (the makers of Viagra) had to invent a disease, called “erectile dysfunction,” to make impotence a more approachable problem. And then they shortened it to “ED” to make it even softer and safer to associate with. It’s a whole lot easier for a man to say, “I am experiencing ED” than to say “I am impotent.”

This is what languaging does.

It changes the way people perceive the thing they’re looking at.

Netflix is another legendary example.

Their POV is that you should be able to watch anything you want, whenever you want. That’s the “frame” of the problem. They then Name & Claim the solution to that problem: “streaming.”

But what Netflix also did was also Frame, Name, and Claim the OLD category experience too. And they did so in a way that was functionally accurate and simultaneously spelled out the problem immediately for customers. They called it “appointment viewing.”

In order for “streaming” and on-demand to work, you also have to believe “appointment viewing” is a problem. And nobody in the ‘90s and 2000s thought “appointment viewing” was a problem. You just assumed you could only watch what you wanted to watch at the hour it was on. As a result, the language people used back then when asking their friends and family about a new TV show was, “When is it on?”

This phrase, this language, no longer exists.

Today, we don’t ask, “When is it on?” The new category overtook the old category—which means new language replaces the old language. Now we ask, “What is it on? Netflix? Disney+? Peacock? Hulu?”

Whoever Names & Frames the problem Claims the language—and wins.

It’s the POV and the language you use to reflect that POV that makes your “messaging” inspire customers to take action — not the other way around.

In your marketing, branding, product descriptions, etc., language has the potential to reflect the unspoken qualities of your category point of view. Our good friend Lee Hartley Carter, communication expert and author of Persuasion: Convincing Others When Facts Don’t Seem To Matter, refers to this as “the understanding that language has the power to create thinking, which in turn inspires action.”

For example, when you walk into a coffee shop, any coffee shop other than Starbucks, what words do coffee drinkers frequently use to order their coffee? “Hi, I’d like a double grande latte please.” But “Grande” isn’t the universal word for “medium.” It’s Starbucks’ word, which a good chunk of the category has adopted. You can’t name a new, different thing, the same as the old thing. Starbucks would never have succeeded unless they designed their own category lexicon. No one would pay $4.00 for a coffee. But they do it for a “Grande.”

Another genius of Starbucks category languaging is that their words are new, fresh, and yet familiar at the same time. The first time we hear, “Venti Mocha,” we have an idea what that might mean. Even though we had never heard it before.

Category queens deliberately use languaging to do a few things:

- To differentiate themselves from any and all competition through word choice, tone, and nuance.

- To speak to (and speak “like”) the customers they want to attract—especially the Superconsumers of the category.

- To further establish their position in the category they are designing or redesigning.

- To insinuate and give context to the rest of the 8 levers: price, profit model, branding, etc., and how the company executes any number of them in a different way.

Languaging can be applied to all 8 levers of category differentiation:

If you want to put your company’s POV to the test, walk through the 8 levers and question how intentionally you are using language to educate customers on the differences between the new category you are creating and the old category that currently exists.

Languaging helps you name the category you are creating (by framing a different problem with a different benefit): There are cars, and then there are electric cars. There’s digital marketing, and then there is chatbot marketing.

Languaging is how you write a compelling mission statement for your brand: Apple’s “Think Different” is a great example (which works because the proper way to say that is, of course, “Think Differently. Apple changing the word to the grammatically incorrect “different” forces the reader to stop.) Same with “Here’s to the crazy ones.” These are some of the best examples of intentional language that ties the audience of the new category and the mission statement of the brand together.

Languaging educates the customer on the experience you are proposing: Streaming video implies a very different experience than getting in your car, driving to your local Blockbuster, and renting a video. Same goes for today’s contactless pick-up at grocery stores and restaurants versus standard “pick up” practices.

Languaging frames the perceived value of your product or service: A medium coffee is perceived to be cheap, but a Grande coffee is perceived to be expensive.

Languaging hints at the benefits that come with radically different manufacturing: An e-book is a dematerialized book. It can be produced infinitely, distributed infinitely, edited and uploaded in an instant, etc.

Languaging also hints at the benefits that come with radically different distribution: OnlyFans calling creators you invite to the platform using your referral link “Referred Creators” signals the benefits of their flywheel and the money you can earn as a result.

Languaging is the “hook” customers, consumers, and users latch onto in your marketing: Substack’s paid newsletters are a different thing than Mailchimp’s free newsletters. Marketing something fundamentally different is always easier and more enticing to the customer than trying to market something that is “better” than what currently exists, but still the same kind of thing.

Languaging also signals to customers how to think about paying for your product or service: Paying a subscription is different than buying products individually. Or purchasing in-game items inside a free video game is different than playing a freemium game with ads. (These are all words and phrases that did not exist until recently, and were purposely used to design new categories.)

Too many marketers, executives, founders, and even venture capital firms think the words a company uses are all about “standing out.”

But you can’t stand out without a clear and different POV. Lexus can scream “Experience Amazing” all it wants and most people will never be able to recall those words and connect them to their brand. Because they do not frame a problem.

You can’t stand out if your POV isn’t being communicated through intentional languaging.

In fact, “languaging” is often more about who the brand, product, and company is NOT for than who the brand is for. The more directly you can speak to the people you are trying to help most, the more likely it is for them to see you as the “undeniable champion” solution of the category you are creating. But the moment you try to widen your net (purely for the sake of “going after a bigger audience”), you begin to dilute your language. Your words become generalized and vague. You aren’t speaking to any “one” person. And if you keep going, and widen your company’s language to be “something for everything,” all of your messaging ends up being another frequency wave in the never-ending hum of white noise—something for no one. (SAP’s message is meaningingful to no one: “Run Simple.”)

When languaging is executed successfully, and is reflective of a well-defined POV of the category, two things happen.

1. You become known for the new language you’ve invented.

You know your languaging is working when customers start using the language you created.

For example, in the early 2000s, Salesforce founder, Marc Benioff created new language for the new category he was creating. He called it “cloud-based software.” (There’s “software” you buy and install on your computer via CD-ROM, and there’s “cloud-based software” you buy and use from any computer, and any browser connected to the Internet.)

In addition, and to further “twist the knife” into the backs of his competitors, he also invented language to reframe the way people thought about the old category by referring to it as “on-premise software.” Notice the distinction: “On-premise software” runs on computers on the premises of the person or organization using the software. “Cloud-based software” runs on a remote facility outside the organization.

What happened?

The entire technology industry started adopting the language he and Salesforce invented.

2. Customers don’t see you as “better.” They see you as different.

The second thing that happens when you successfully use language to change thinking is you dam the demand.

When you use intentional language to modify the existing category (“cloud-based software”), you create a chasm between the old and the new. For example, an “e-bike” is not better than a “bicycle.” It’s something different. It has different benefits, different use cases, even different price points, profit models, and manufacturing processes. One single letter and a dash tells the reader/customer/consumer/user “this thing is not like what came before it.” Same goes for “frozen food” and “fresh food,” or “sunglasses” and “glasses.” These languaging modifications make the customer STOP, tilt their head, and immediately wonder, “This is for something different—do I need this?”

And since you were the one who invented the language, you become the trusted authority to educate them on the definition of that new language—and subsequently, that new category.

Languaging is how you change the world.

At the highest level, languaging is used to move society forward.

Not long ago, people living on the streets were called “whinos” and “bumbs.” Today, they are called, “people experiencing homelessness.” This new languaging changes how people perceive the problem and subsequently treat others and work toward a solution.

Remember: A demarcation point in language creates a demarcation point in thinking, creates a demarcation point in action, creates a demarcation point in outcome.

There was also a point in time when the minimum wage for women was lower than it was for men. Women got paid less. Until a movement mobilized around some strategic, future-changing languaging: “Equal pay for equal work.” These words were so powerful, they changed the law.

And sometimes, languaging emerges through new combinations of words into a portmanteau.

- Gamification

- Infotainment

- Brunch

- Podcast

- Frenemy

Whenever language is bent, it tweaks the ear to listen—and to consider the different.

We all have AIDS.

In 2005, fashion designer, Kenneth Cole, launched an AIDS awareness campaign in conjunction with the American Foundation for AIDS Research. The POV was: “We All Have AIDS… If One Of Us Does.”

Notice, this is not “a clever message.” This is a radically different, crystal clear point of view of the world, reflected through languaging: the strategic use of language to change thinking.

The campaign then featured figures such as former South African President Nelson Mandela, South African advocate Zackie Achmat, South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, as well as actresses Ashley Judd, Sharon Stone, and Elizabeth Taylor, and actors such as Tom Hanks, Will Smith, and so on, all with the chief aim of minimizing the stigma associated with the disease. Kenneth Cole & the American Foundation for AIDS Research wanted to dispel the myth that AIDS is only an issue for HIV-positive people.

How?

By saying, very clearly, “If anyone is infected, we are all affected. If it exists anywhere, it exists everywhere.”

Languaging + Math = Story Arc.

One last thing.

If languaging is how you communicate your differentiated POV, then numbers are how you communicate the urgency of your POV.

Numbers are what give your story an arc.

In everything you say, you are either communicating one of two story arcs. Either you have no treasure, and you’ve found a map that says there’s lots of treasure over there. Or, you’re Chicken Little with lots of treasure warning everyone the sky is falling. Numbers are the evidence, and amplify the language.

To be clear, we’re not saying you need to understand how to perform statistical analyses or do napkin calculus. (Pirate Christopher failed 3rd-grade math, and Pirate Cole still counts with his fingers.) Languaging masters simply need to understand whether something small today could be gargantuan tomorrow, or something big today could be small, even nonexistent tomorrow—and then strategically use language to educate readers, listeners, customers, and consumers on the importance of that story arc.

The Origin Story of McKinsey

For example, McKinsey & Company was a firm founded in 1926 by James O. McKinsey, a University of Chicago accounting professor. McKinsey started out as a group of bean counters and accountants, not the defacto standard of world-class professional services we associate today with McKinsey.

Who built McKinsey into the powerhouse firm it became was Marvin Bower, the Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School graduate hired by James O. McKinsey. Bower had a powerful a-ha. He discovered a “missing.” He noticed that while clients paid for accounting services, what they often valued more was business advice from a trusted source.

Mavin Bower is the category designer of management consulting.

He was a languaging maniac.

Under his guide, projects were not called “jobs.” They were engagements—a word that is much more relational than transactional. Internal groups with specific industry or functional expertise were called practices (Like doctors, this is the intentional use of language to create the perception of value)—emphasizing that learning was a never-ending endeavor. Finally, McKinsey was not a “business.” It was a firm—highlighting the core values that held the company together. Even today there are few firms who are as rigorously committed (some might say cultishly committed) to the original language Marvin Bower put into place.

All of these distinctions helped McKinsey thrive and create the $255 billion dollar global category known today as Management Consulting. And notice history remembers the lawyer, Marvin Bower (lawyers are trained in the discipline of language), not the accountant, as the “father of management consulting.”

All legendary languaging represents 1 of 4 math equations:

- Addition

- Subtraction

- Multiplication

- Division

If your languaging does not tell one of these 4 story arcs, no one is going to listen to what you have to say. There is no urgency. You are responsible not just for strategically using new words to frame new problems (or reframe old problems), but also reveal whether the slope is positive or negative—are the numbers going up or down? Where is this story going? And your ability to comprehend and communicate that slope is what makes your languaging matter.

- Addition: “With C4 pre-workout, your workouts will last longer.”

- Subtraction: “With Spanx, pounds seemingly disappear. A flat stomach in seconds.”

- Multiplication: “With an acoustic guitar, only some people can hear your music. With an electric guitar, an entire stadium of people can hear your music.”

- Division: “Condoms are 98% effective at protecting against and reducing the spread of most STDs.”

The power of language can be multiplied (pun intended) when paired with numbers to create new langauging.

Numbers tell powerful stories too.

So as you sail forward in life and business, we ask that you pay special attention to the Framing, Naming, and Claiming of things. Because we get taught to think by the words people use with us (which means you can teach others to think by the words you use with them).

A demarcation point in language creates a demarcation point in thinking, creates a demarcation point in action, creates a demarcation point in outcome.

Arrrrrrr,

Category Pirates

Why Marketing Leaders Get Fired

Case in point: The Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. They showered awards on Burger King, giving them stuff called the “Titanium Grand Prix” and “the very first Creative Brand of the Year.”

Burger King has 1.16% market share. McDonald’s 21.4%.

Burger King does $10 billion in sales. McDonald’s $37 billion.

Burger King has been stuck in the “Better Trap” for about 24,647 days, AKA 67 years.

Also, Burger King features McDonald’s in an insane percentage of their ads. Which serves to educate consumers that McDonald’s is the Category King.

Burger King might as well Venmo their marketing budget to McDonald’s.

Yet “creative marketing leaders” give Burger King “creative brand” awards.

This shows how deeply disconnected some marketers are from business outcomes that matter. Like revenue, market share, and market cap.

Legendary marketing is not about creative. Legendary marketing is not about branding.

Legendary marketing is about designing and dominating a category that matters.

Never Give Up On Something You Can’t Go A Day Without Thinking About

Winston Churchill famously said, “Never give up on something you can’t go a day without thinking about.”

Although he didn’t say anything about what to do if the thing you can’t stop thinking about makes you batshit crazy?

As in, your “something” owns you. It’s in your head so much, your “something” thinks YOU, not the other way around.

Is this the difference between passionate and possessed? Is trusting this “something” how to Follow our Different?

What Churchill also doesn’t say is, what to do if 8 out of 10 ten times you share your “something”, you fail.

For 30 years?

Then what?

Well, my “something” is Category Design. And this week is the 5th anniversary of “Play Bigger”. It introduced Category Design to the world.

The book was my last-ditch effort. My hope was to help pirates, dreamers and innovators make a difference.

And, I figured the book would fail.

A 30-year .200 batting average will do that to you. I assumed, I’d end up being the weird guy drinking in the corner talking to myself about stuff most people thought was nuts, or irrelevant.

Before Play Bigger came out, most people didn’t get it. And while I was having success in my career as an entrepreneur and a CMO, most times I shared the thinking behind that success – Category Design, people’s eyes glazed over. Or they thought I was talking about nose-picking marketing or worse, “messaging”.

So, I figured Category Design would remain my secret and the secret of a handful of people who “got it”.

I tried and failed more times than I can count to leave Category Design alone. Being obsessed with something – for 30 years –- that most people think is stupid — can make you fucking “crazy”.

Then Play Bigger took off. And our podcasts, Niche Down and now Category Pirates took off.

Play Bigger made it into the top 1% of business books. Niche Down hit #1 in marketing books on Amazon. Lochhead on Marketing hit #1 on Apple’s podcast business chart and, there was the few days Follow Your Different broke the top ten on the over-all Apple charts and beat out Oprah!

If you read, listen to, got anything out of, or shared any of our work, from the bottom of my whisky stained heart, THANK YOU.

Now… here is a truth I’d like you to know.

I’d be lying if I led you to believe that Category Design is so legendary, it just became a massive viral hit. That the “product” called Category Design, was so legendary, it marketed itself. Well, I’m a lot of things, but liar is not one of them.

Some Digital Entrepreneurs, motivational “Hustle Porn Stars” and get-rich-quick “Growth Hackers” make it seem like there is a cheat to success.

I even fell for it. As I was starting off as a writer and podcaster, I thought we could hire some super ding-dong, growth hacker whiz kid to make us go viral. Then BOOM! Success.

Not so much.

Too often people who achieve success talk about it as if everything went up and to the right.

It’s almost always a lie. It takes work. Smarts. Luck. And a lot of help.

What did it really take to Category Design tip?

- 30 years in the trenches

- Then… 7 years, (approx. 2,555 days) of hard work

- Legendary partners and co-Creators

- Support from countless legendary people

- Support from over 50 top podcasters

- Over 50 speeches

- A ton of PR

- Producing over 500 of our own podcasts

- A ton of good luck

- A ton of readers and listeners sharing

- And, the love and support of SAP (This is funny if you read the “10 reason not to read this book” at the start of Play Bigger)

So yes, becoming an over-night success is easy! (Coughing and saying “bullshit” at the same time).

Most importantly, please know, I know that it’s tough feeling crazy.

Feeling different.

Feeling like the world doesn’t get you. Some people find their place in the world, but many of us have to MAKE our place.

If you’re that kind of person, if you’re a person trying to make the world a different place, I believe:

The future needs you.

Please do not stop.

The future needs you.

The future needs more people working on the exponential. Creating breakthrough categories that move humanity forward.

And, if you have a “something” that makes you crazy, you might find solace, in these two musing that I often hold on to.

From Charles Bukowski:

“Some people never go crazy. What truly horrible lives they must lead.”

From Steve Jobs:

“Here’s to the crazy ones.

The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers.

The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently.

They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo.

You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them.

About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward.

While some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius.

Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.”

Best wishes for legendary success, bless you and…

Thank you.

Christopher Lochhead

June 2021

PS: The follow up from me (and my partners Eddie & Cole) to Play Bigger is the Category Pirates Newsletter.

If you’d like to try it free for 30 days, respond to this email with “YES” and we’ll get you on board the Category Pirate Ship ?☠️

The Problem With Platforms: How Direct-To-Creator Is Redesigning Legacy Media & Social Media At The Same Time

Originally posted in Category Pirates: it’s not a long newsletter, it’s a short book—delivered to your inbox each week.

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and fellow Category Pirate,

Business media “platforms” and social media platforms have a problem.

The way content gets created, distributed, and monetized today is being radically transformed—and most people haven’t noticed yet. So hop aboard the pirate ship, grab a cocktail or a coffee, and let’s talk about the profound media category change that is going to affect every business, brand, and business person of influence.

We’ll start with Substack.

Do a quick Google search for “Substack”—the venture-backed paid newsletter startup whose “mission is to democratize publishing tools to help writers manage their own subscription-based businesses”—and you’ll see the category battle happening in plain sight:

- “Journalists Are Leaving the Noisy Internet for Your Email Inbox” (The New York Times)

- “Why We’re Freaking Out About Substack” (The New York Times)

- “Substack Offered 6-Figure Advances to NY Times’ Liz Bruenig, Taylor Lorenz” (The Wrap)

- “Substack Is A Scam in the Same Way That All Media Is” (NY Mag)

- “What Substack Is Really Doing To The Media” (Slate Magazine)

In 2019, Substack raised $15.3 million with high hopes for redesigning the way creators monetized their email lists. Even just two years ago, creating a paid newsletter and running your own content-based subscription business was very difficult (Category Pirate Cole tried, and ended up having to duct-tape a handful of tools together). This was before Twitter jumped on the bandwagon and acquired Revue, a newsletter platform they’re working on integrating into their ecosystem, or before ConvertKit (another email newsletter platform) launched a paid newsletter function. Substack saw a “missing,” a hole in the market caused by the neglect of the media and social platforms, and created a new category out of that neglect.

And they’ve done a legendary job marketing their radically different POV.

So much so that in March of 2021, Substack announced its Series B: a whopping $65M raised at a $650M valuation.

The TechCrunch article announcing the investment refers to Substack’s category as “alt-media” (probably because it would hurt too much to call themselves “legacy media”). Others refer to Substack as Independent Journalism opposed to “Professional Journalism” (whatever that means anymore). Or, more broadly, Substack is one of many new tools and innovations spearheading what is being called The Creator Economy: the part of the Internet where content (and therefore attention) is paid for directly by customers, not indirectly via advertising revenue.

Up until now, creators have not been paid (fairly) for their work. The platforms have been plundering the booty.

There is almost no finer (or more overt) example than pornography.

There’s a quote that has long gurgled in the underbelly of the Internet that if you want a signal for where technology is headed next, just follow porn and gaming. Well, since the dawn of the Internet, porn has been a rough industry for creators. Category Pirate Christopher had former adult actor and now digital media star, Mia Khalifa, on his podcast where she explained how she became one of the most-watched adult performers on the Internet amassing hundreds of millions of views—for which producers paid her only $12,000. Economic servitude is just one type of exploitation that happens in this “behind closed doors” industry.

Now, if you were a savvy porn creator back in the day, you might have launched your own website, served your own content, and processed payments directly. But similar to the problem Substack saw in the world of writing and publishing, the tools for managing a subscription-based video content business have never been easy to use. Instead, many porn content creators have turned to the social-media-equivalent for their industry: cam sites.

Being a porn creator reliant upon cam sites isn’t much different than being a business writer or photographer reliant upon Twitter or Instagram’s algorithms, or a musician relying on Spotify and Apple Music to be discovered. These cam sites do what every other social media platform on the Internet does for its creators: promise exposure (while taking all the cash). It’s then the creator’s responsibility to discern what to do with that exposure, and how to leverage it for their own personal gain—very little of which happened on-platform.

And for a long time, this was seen as the trade-off.

Until OnlyFans came along.

Porn paved the way, but now everyone else is following.

OnlyFans started in 2016 to fix the monetization problem for creators—and successfully created a new category as a result. Since then, OnlyFans has become one of the fastest-growing media companies on the planet. With more than 90 million registered users, 1 million creators, and more than $2 billion (yes, with a B) paid out to creators directly, OnlyFans (according to The New York Times) has already Changed Sex Work Forever.

The difference?

While cam sites take 80% of creator earnings, OnlyFans pays out 80% of earnings to creators.

A flip in economics like this is not just Category Design. It’s Category Violence.

No different than what Substack is doing in the written media space, OnlyFans made it possible for creators to launch and manage their own subscription businesses. Creators can collect monthly subscriptions and tips, as well as income on pay-to-view messages. Most importantly (like an MLM company), creators on OnlyFans have a referral code where they can collect 5% in lifetime royalties on earnings generated by any new creator they bring to the platform. (This is a brilliant business model innovation, paying early Superconsumers to be the leverage needed to tip the category.)

Furthermore, OnlyFans did a “Dam the Demand” move that revealed all the underlying problems with the legacy category’s business model away from advertising (transactional focused) and moved it to a new & different model built on recurring subscriptions (lifetime value focused).

Instead of exploiting creators, OnlyFans empowered them.

Creators own their audiences, allowing them to build their own individual “data flywheels” and achieve a completely different level of personal agency and financial freedom. From a career perspective, we would go so far as to say that OnlyFans built a mechanism for helping creators execute their own Personal IPOs.

And while OnlyFans leans “adult,” the platform’s functionality can be used for whatever type of content the creator wants, including: cooking, music, beauty, comedy, etc. (Remember, once you “Dam the demand” you can expand it).

As a result, it’s common for emerging creators to earn upwards of $10,000 or $20,000 per month on OnlyFans, with the highest-grossing creators bringing in millions and millions of dollars—not from ad revenue, but from customers paying creators directly.

Direct-To-Creator

Patreon. Cameo. Gumroad. Mighty Networks. Shopify.

Today, there are dozens of tools creators—ranging from writers to educators, artists, musicians, and beyond—can use to turn themselves and the content they create into independent businesses. As a result, the way creators think about, prioritize, use, and remain loyal to media and social platforms is changing.

And the legacy platforms are teetering.

In the past, these platforms were seen as an end in and of themselves. “I have 10,000 followers on Twitter. I’m a columnist for Forbes. Cool!” But over the years, creators have learned (the hard way) they don’t take followers as payment at the grocery store. In fact, you need hundreds of thousands of followers, if not millions, to earn a minimum wage monthly salary from influencer/brand sponsorship deals. And creators are slowly waking up to the fact that while they’re getting wrecked at sea, the platforms are getting rich. Facebook is now worth $900 billion off advertising revenue generated on the consumption of free, user-generated content.

Wired editor Kevin Kelly’s groundbreaking piece, “1,000 True Fans,” spoke of this Great Awakening all the way back in 2008. (To which Andreesen Horowitz’s Li Jin responded last year with a piece titled, “1,000 True Fans? Try 100.”) When payments go Direct To Creator, you don’t need hundreds of thousands or millions of followers to earn an income—because you are no longer a cog in the machine chasing your sliver of advertising revenue. All you need are a couple hundred Superconsumers paying you $10 to $25 per month, and voila: you’ve now surpassed the income of your day job and can become a creator full time.

This is a life-changing outcome.

As a result, big name social media platforms and Tier 2 business media publications (like Inc, Forbes, Fortune, etc.) that have built businesses off the exploitation of creators are being devalued by the day. Every hour, every minute, every second, another creator somewhere on the Internet gets introduced to this idea of monetizing their content and reputation directly, changing the way they value and use these media platforms from being destinations in and of themselves, to using these platforms for free marketing—from which they can siphon customers, attention, and revenue.

Creators are now doing to platforms what platforms have long done to them.

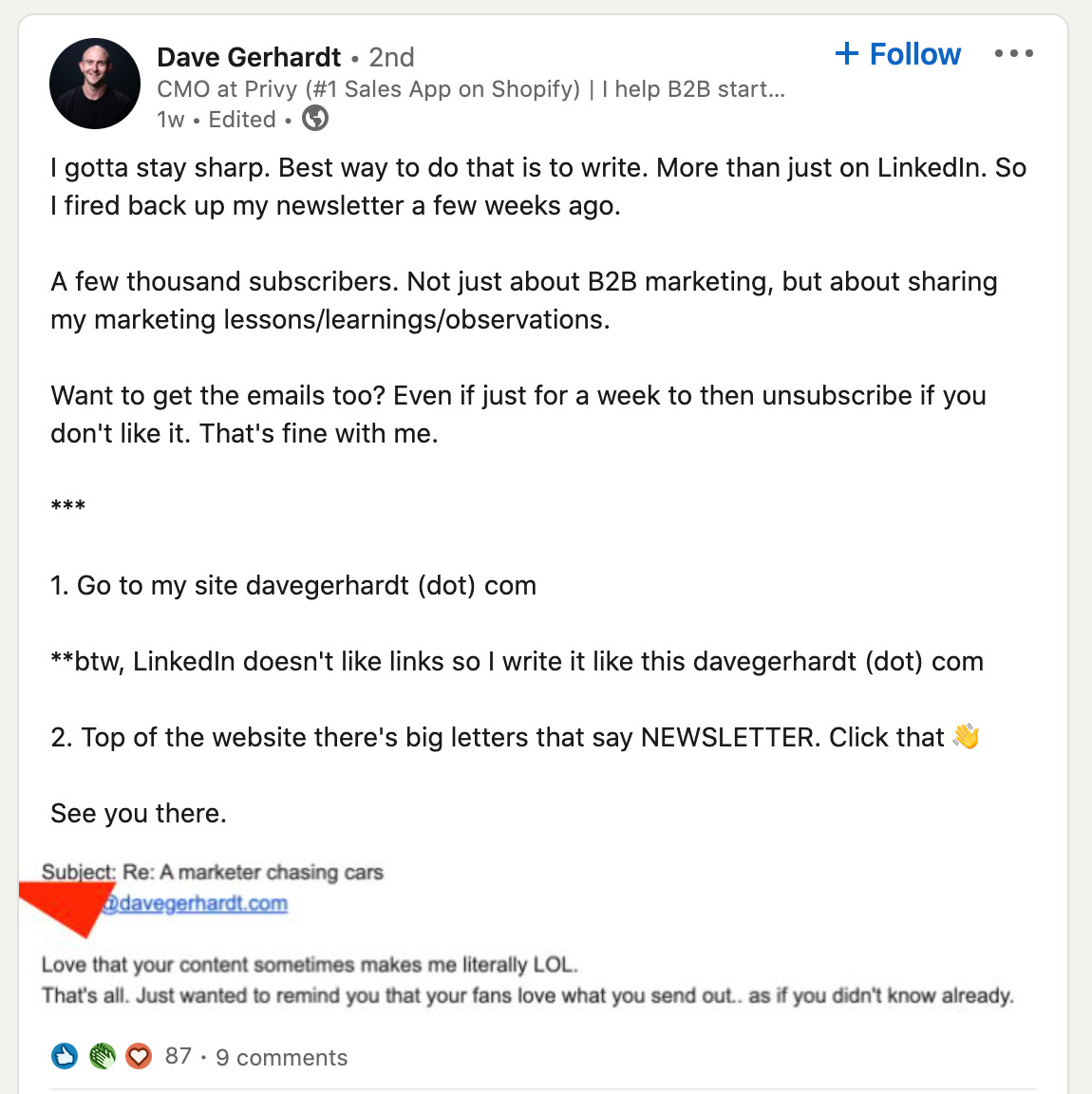

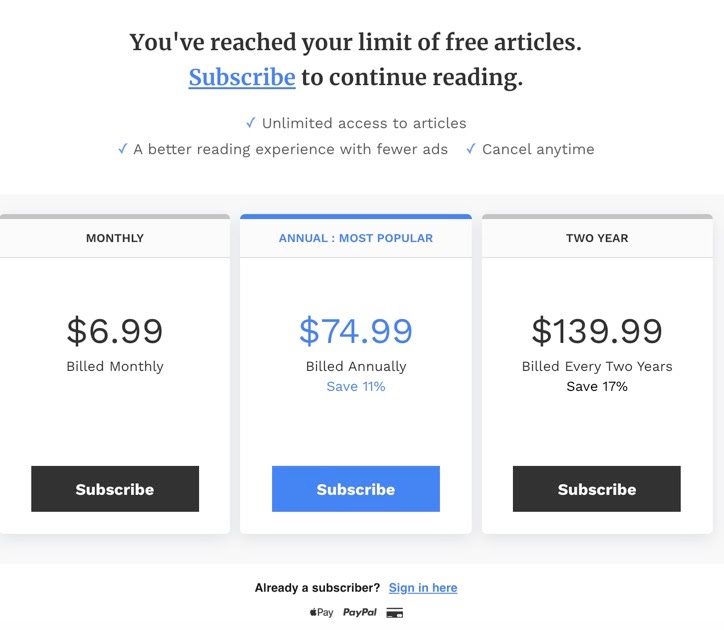

Exhibit A:

This is what we call a FROTO: the way category designers educate customers to move from the old category to the new.

The New York Times vs Substack, the porn industry vs OnlyFans, these are only the beginning.

This category violence is happening everywhere.

As creators ourselves, specifically within the niche of business wisdom & category design thinking, we see this Direct-To-Creator evolution happening rapidly in the category of legacy business media. For the past two decades, conventional wisdom has said that writers should submit their content for free (or close to it) to major publications—the trade-off being the creator gets to tap into the publication’s wider audience, while the publication acquires one more asset they can monetize with ads.

We are watching the entire legacy business media landscape (and maybe soon the entire social media landscape if platforms don’t act fast) collapse.

Let’s take a quick look at how we got here:

How Business Media Plundering Became A Historic A Self-Inflicted Blunder

In 2005, Andrew Breitbart, Arianna Huffington, Kenneth Lerer and Jonah Peretti founded HuffPost.

The “innovation” here was, instead of being a publication reliant upon staff writers, editors, and the occasional byline submitted by a business executive or political leader, HuffPost was built to be a news aggregator and community blog. Instead of being in the business of creating content, HuffPost was in the business of curating content. As a result, HuffPost grew like a California wildfire. In 5 short years, the site had more than 37 million monthly visitors, 1 billion page views, and was generating roughly $60 million in revenue per year with a valuation just shy of $100 million—before being acquired by AOL in 2011 for $315 million.

HuffPost set the trajectory for what it means to build a “successful media company” in the digital age. And in 2012, almost the exact same story was repeated by Elite Daily: a community blog/content aggregator for Millennials that leveraged free, guest contributed content. Two short years later, the site had more than 41 million monthly readers, generated $7 million in advertising revenue, and was acquired by the Daily Mail for “$40 to $50 million, all cash,” according to Business Insider.

Turns out, banking beaucoup bucks is easier with slave labor.

Almost every publication that grew quickly in the 2010s adopted this model.

BuzzFeed. Refinery29. Thrillist. Observer.

They all saw what HuffPost and Elite Daily had done and attempted to replicate their success. Staff writers were slowly replaced by free, “contributing” writers. Editors (many of whom were fresh out of college) were given carte blanche to approve submissions. (Pirate Christopher experienced this when he became a contributor to Fortune, and was assigned an “editor” who was so green, she didn’t know what a category even was. Christopher quit instantly.) More content meant less time to give critical feedback and improve quality. Decreased editorial standards led to an acceleration of a “volume wins” approach to publishing. And all of a sudden, the entire written media landscape was in a race to the bottom where only three metrics mattered:

- How many pieces was the publication publishing per day?

- How many page views was that generating?

- How much high-margin ad revenue could be generated off those page views?

Things like quality, cohesive voice, and a differentiated point of view became things of the past.

Here’s a little inside baseball as to the inner-workings of the legacy business media category:

Category Pirate Cole witnessed this first-hand as one of roughly 400 contributing writers for Inc Magazine at the peak of industry-wide desperation for free content in 2016. Of the 400 or so writers contributing to Inc, only a small handful were paid—Cole being one of them.

The model was intentionally designed to avoid rewarding creators financially for their work. In order to qualify for payment, you needed to be writing and publishing more than 8 pieces per month for the publication (2x per week)—and for the vast majority of contributing writers, this wasn’t feasible (Category Pirate Eddie fit into this bucket for only a short period of time). Anyone of merit building or running a company wasn’t going to be able to create 8 new pieces of content for Inc Magazine per month, month after month. So most contributing writers took their trade off (“I get exposure in exchange for my free content.”), while Inc (and many other publications) focused on scaling their contributor base by targeting credible writers and thought leaders who failed to meet Inc’s paid tier requirements.

If you were one of the writers producing more than 8 pieces per month, like Pirate Cole, you were paid on performance—approximately $0.01 per page view (which was considered “industry standard”). On the surface, this sounds like a terrific deal because the perception is that these publications generate millions, or even tens of millions of views (which is the number editors luring “free contributing writers” tout as the primary benefit of publishing there instead of somewhere else).

What doesn’t get shared with creators are much more important metrics like Bounce Rate and Average Visitor Duration. According to SimilarWeb, Inc Magazine today has an 84% Bounce Rate with an Average Visitor Duration of 47 seconds (not to mention their total monthly views has fallen from 20M in 2018 to 13M in 2021). What this means is, when a reader comes to Inc Magazine, they spend 47 seconds reading and 84% of the time, they immediately leave the site after reading just one page.

As Pirate Cole wrote about in his book, The Art & Business of Online Writing, of the 409 columns he wrote exclusively for Inc over the course of two and a half years, only 44 of them exceeded more than 10,000 views. And of Cole’s Top 10 highest-performing columns, nine had to do with personal development (the widest, most general and undifferentiated content type on the Internet).

As one of Inc Magazine’s Top 10 contributing writers, using an average of 30,000 page views per month multiplied by 30 months at a penny per page view, two and a half years of obsessive content creation = $90,000. Divide $90,000 by 2.5 years and that’s effectively a $36,000 per year income—or approximately $17.30 per hour. (Minimum wage in California, where Pirate Cole lives now, is $15.00.)

Meanwhile, doing some basic math using Inc’s media kit here, 2.7 million to 5 million total page views driven for the publication means Inc made anywhere from $400,000 to $700,000 in ad revenue using their CPM of $147. If Pirate Cole took home $90,000 over the course of 2.5 years, that means he received 12% to 22% of the revenue generated off his content. And if we use Inc’s top CPM of $250, then Cole generated anywhere from $680,000 to $1.25 million in revenue, meaning he received 7% to 13% of revenues.

Here’s a headline: the economics of being a paid contributing writer for a legacy business media company are worse than that of an adult performer on a cam site.

How Business Media Neglected Its Category

For the past fifteen to twenty years, very little about this model has changed.

Media platforms of all shapes and sizes have treated content creators the same way the porn industry has treated adult performers: mercilessly and without concern.

Creators have never had the out-of-the-box ability to turn attention, impact, and content into a business. Best-case scenario has always been churning out YouTube videos or Inc Magazine articles and hoping your share of the ad revenue pays the rent. Furthermore, these platforms have reinforced the narrative that creators should be happy with this arrangement.

And like a prisoner struck with Stockholm syndrome, creators and consumers have become addicted to short-term vanity metrics like views, followers, Likes, and so on—all while receiving pennies on the dollar (or nothing at all) for the value created.

But now, the jig is up.

Or, as The Boss sings, “Come on for the rising!”

Go explore any Tier 2 business publication today and almost all of them are copies of each other—aggregators and curators that have outsourced their product to the lowest common denominator of lousy content creators. Put a Forbes article beside an Inc article beside an Entrepreneur article beside a Fortune article beside a FastCompany article, remove the logo, and you have no idea which is which. There is no unified voice, no recognizable editorial guidelines, no differentiated point of view. Which means these publications have all chosen to compete on one metric and one metric only: volume.

As a response to this Great Awakening in the Creator Category, legacy business media publications are scrambling to find their way back.

Both Inc and Forbes have quickly pivoted to paywall models charging subscribers for access to their content (the same undifferentiated content they’ve been publishing as fast as possible). But consumers are getting hip to the scam. For example, when Forbes pops up their paywall, savvy consumers say to themselves, “You want me to pay $75.00 to read articles that are written for you, for free, with little quality control or fact checking? And I get no direct relationship with the writers?…I don’t think so!”

Forbes has even gone the extra mile with its “Forbes Agency Council” program (positioned as “Invite-Only”) where “business leaders” can pay a fee to publish whatever they’d like on the site.

This is HuffPost squared.

They’re just trying to scratch out a few more notes on the violin as their ship sinks.

We have a Pirate recommendation (which the legacy media brands will never implement).

For those of us who remember the days where landing a piece in Forbes magazine meant something, we are saddened by the fact that legacy business media is committing category suicide.

These publications are already dead. They just don’t know it yet.

As we have written about in previous letters, this Direct-To-Creator tailwind and the headwind of undifferentiated business content is creating a perfect storm of either opportunity or ruin. If you follow the direction Substack, OnlyFans, and others are pioneering by putting the relationship between creator and consumer first, you will likely survive and emerge a stronger, even more profitable business. If you double-down on your existing content & business strategy of aggregating en masse and then trying to charge readers for access (unless you’re a Tier 1 business media platform like The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, or Harvard Business Review), you’re probably going to sink.

The same, by the way, is likely true for higher education, where the very top tier of schools with strong graduate schools and a heavy research & development focus will survive and innovate because they can attract the best professors (the creators). But great professors will also soon realize they can go Direct to Creator too, and earn more money, working fewer hours, with more career autonomy. University of Toronto Professor, Jordan Peterson, has become a controversial digital mega star by building his own Direct To Creator relationships and monetizing directly. Now he even sells t-shirts, stickers, and posters. This will be the nail in the coffin for the many undifferentiated colleges/universities that are overpriced and deliver poor outcomes. But this is a topic for another letter.

If we were the category designers for Inc Magazine, Forbes, or even The New York Times, we would encourage these publications to let go of “the way things have always been” and to start empowering their highest-performing creators. Help these writers become independent. Help them leverage the audience of the publication to build their own recurring, subscription revenue streams—and then, similar to OnlyFans or Substack, take a *small* piece of the action (not the entire pie).

There is a world wherein the front-end of The New York Times becomes no different than the home screen of Netflix: a curation of all the most prolific, most popular creators in the business/news media world. But the back-end of the publication becomes a combination of Mailchimp, Stripe, Substack, and Medium. Writers can build their own email lists, their own paid subscriber bases, accept tips, sell additional content/research, and build a library of content that earns dividends well into the future—all while continuing to write for the publication. (Meanwhile, Pirate Cole’s library of 409 Inc Magazine columns continues to generate 20,000+ views for the publication month after month, year after year, of which he receives $0.)

In this world, The New York Times or Forbes operates closer to a record label or even an investment fund for writers and creators than an attention-starved, advertising revenue addicted publication.

But that doesn’t seem to be what’s happening.

Instead, even the most prestigious business and news publication on the Internet, The New York Times, is prohibiting its writers from starting Substacks and monetizing their content elsewhere.

We’ll see how long that lasts.

These very same headwinds and tailwinds are coming for the social platforms too.

Every time you see a creator with a Linkedin post that says Link in comments,” what you’re witnessing is the creator fight the power being exerted over them by the platform. This is why LinkedIn and Twitter are starting to experiment with new monetization opportunities for creators (albeit however small, like Twitter’s new Tip Jar feature). And who knows if Facebook/Instagram and TikTok are even considering putting the creator at the center of their business model instead of the advertiser.

We think they should.

The seminal question of course is… “Is it too late?”

Savvy creators are increasingly using social platform reach to move people from the walled gardens to the tools that empower them to communicate and monetize their audiences directly, reducing the long-term value of social media in a meaningful way. (Remember: social media platforms are only as valuable as the number of people spending time consuming content there. If all the good creators leave, the quality of the content goes down, giving users less reason to stick around, which impacts advertising revenue, and so on.)

In a sense, these “free” social media sites are slowly becoming “content dating” sites, where consumers and creators can get to know each. Then, when the relationship starts to blossom, the consumer and creator can disintermediate the platform.

As we reflect on this massive category change, we also wonder what this will mean for brands and how they choose to access audiences who are moving from free, wide-reaching media publications and social media platforms to paid newsletters and private communities. At a minimum, marketing investments will continue to shift, further driving the demise of media platforms and challenging the ad supported models of legacy digital media platforms.

After almost two decades of this insanity, it’s abundantly clear that being a low quality content puppy mill is a bad business model for everyone involved: creators, consumers, and every other platform in the category.

Legendary, missionary businesses create abundance. Dying, mercenary businesses fight over it. For a business to thrive, the ecosystem needs to thrive as well. Exploitation doesn’t work as a strategy.

If you win when your ecosystem loses, you are not long for this world.

Arrrrrrr,

Looking For A Growth Strategy? Try Category Creation

Category creation is the ultimate growth strategy. According to research published in the Harvard Business review, by our friend and fellow Category Pirate ?☠️ Eddie Yoon.

Defining What It Is

Category creation (aka category design) is a management strategy that has been employed by the most successful companies for years. It involves the creation of new categories of products and services to introduce to the market. It’s about designing your own game Vs. playing someone else’s. It’s about introducing the world to a new, different approach.

Category designers also earn the vast majority of the economy in the category. 76% to be exact. Of the total value created – as measured by market cap.

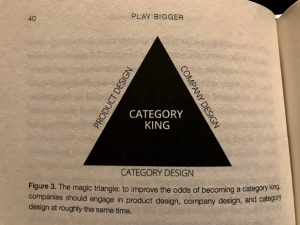

Products don’t make new categories by themselves. Legends design a new product, company (business model), and category at the same time.

Category designers present their products and services under a new category and educates the market on that category.

Why It Is Ideal For Growth Strategy

Today’s market is smart. People are aware that most companies are fighting with each other to get your money. But with category creation, you present a real problem and an innovative solution at the same time, so you immediately distinguish yourself from all other companies.

You become the brand that cares and aims to improve people’s lives. Empathy and radical generosity are hallmarks of companies pioneering new categories. Thus, even as you educate the market about your category, you inevitably build brand awareness. That brand awareness goes deep as it is about values and not aesthetics.

And the more valuable the category, the more valuable the brand. Most people don’t realize that categories make brands. Not the other way around. Xerox and Dell have great brands. But no one gives a shit about them any more. Because they are no longer leaders in categories that matter.

Pulling in another company’s loyal customers is a difficult feat, but you already know that. In a highly competitive market, your best bet to achieve growth is to come up with your own market by creating a new category. Carve out your own niche in the market, and nurture your loyal customers. Educate them about your category, company, and products, and make sure that you evangelize how you’re DIFFERENT.. Not better.

There is no such thing as a legendary business without loyal customers. Customers are, in fact, another reason why creating a new category works as a growth strategy.

Categories about customers. And their problems. Brands are about us. Category design is about creating new value for customers where none had existed before. Branding is about shouting “WE’RE AWESOME. BUY FROM US”.

Companies who are “us” focused, will always get crushed by companies who are “them” focused.

When people truly care about your category, they will also easily value your company, and they will not hesitate to tell others about you. Loyal customers will help you reach a wider market that needs your products or services. You will not need to exert all your effort on marketing because the people who value your category will push your company to the forefront.

Grow Your Company

Category creation is, first and foremost, a new lens on business. It requires creativity and spunk. You need to be ready not to play by any of the existing rules and to be clever enough to create your own. Christopher Lochhead can help you apply the concept to your company.

Category Creation Versus Category Design

Category creation and category design are often confused or thought to be synonyms of each other. Those two, however, are different but closely related.

Category Creation

Category creation often gets conflated with “first mover”. That is to say, that a category is created by the first company to introduce a new offering. That is radically different than anything that has come before.

That’s why we prefer the term category design. Because dominating a new category is not necessarily about being first to market with a product. It is about being the first company to have your definition of a problem, and therefore solution, tip at scale.

And categories can be redesigned. Apple did not create the mobile phone. But they did redesign the category with a fresh point of view and a radically different product.

Category Design

Is a management discipline that focuses on establishing different categories of products of services. It involves educating the market about a new, often ignored problem as well as a solution that you can provide. It is often associated with a breakthrough product or service. However, your offering has to be combined with a breakthrough business model and a breakthrough big data about future category demand.

Many legendary category designers design the space around their product and company based on a noble purpose. It is about defining and developing the category you created so that people understand it along with your product and company and then demand it.

Category design comes after you have created a new category and product. It may be associated with company design in that an enterprise must develop its business model, culture, and point of view in a way that aligns with the new category.

Breaking Through With Category Creation And Category Design

You may have heard this many times: category design will push your company to success. The principles of it have been hiding in plain sight for a long time, and they have been proven effective regardless of the industry. Recently it has broken out of Silicon Valley to become a mainstream business discipline. That is because they are not anchored to just the innovation of new products.

Category design strategies are founded on perspective — a new point of view. That just like products, services, and business models, market categories can be proactively created.

That is what makes them effective and applicable to any company. The human brain forms connections between categories and its own experiences. Thus, people remember categories—especially those that solve their personal problems—more easily than they remember brands. Category design solidifies your company’s brand identity as the pioneer in the new category you came up with.

Many companies succeed with category creation and design because they generate a new market for your company, one that truly needs your product or service. You are, in essence, marketing to a captive market. Category designers win by radically differentiating themselves by creating a perception that they are very difficult to replace. They do not compete in any traditional sense of the word.

They are unique. And in a world where more and more legacy categories are becoming commoditized, being perceived as different, unique. Is the ultimate advantage.

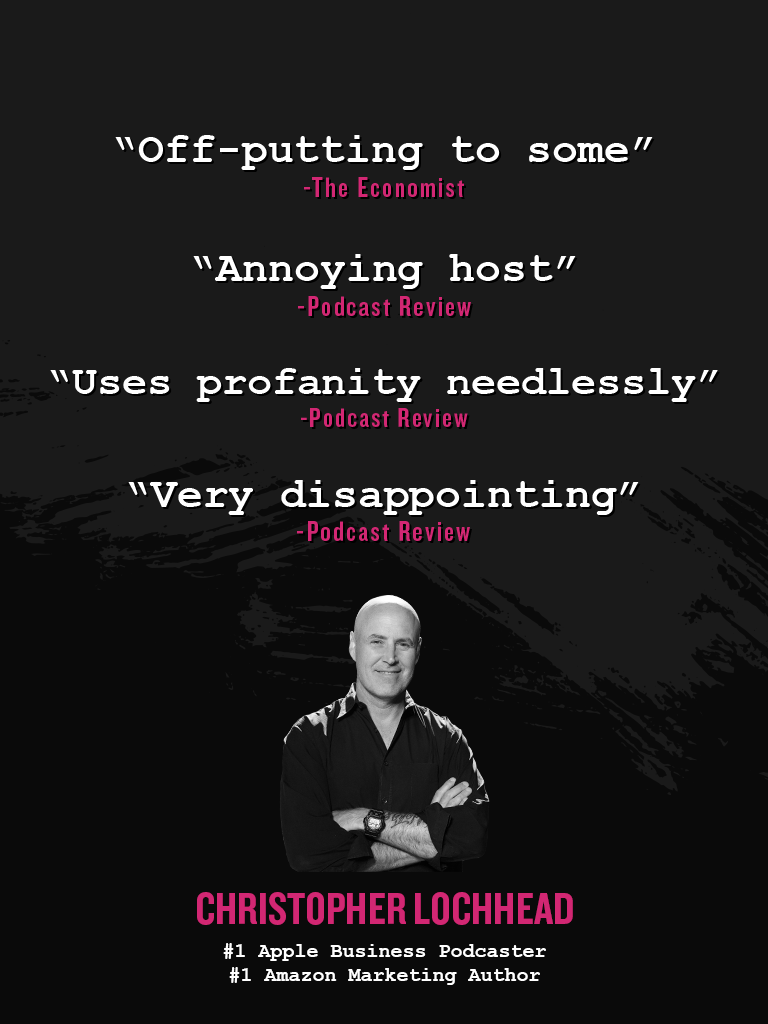

First Ad Campaign Featuring Negative Reviews By Podcaster

#1 Charting Business Podcaster Christopher Lochhead wants to empower creators to embrace the haters.

In another first for the Podcasting category, Christopher Lochhead, announced a new marketing campaign in Podcast Magazine featuring negative reviews.

“There are many creators who get crushed by one negative review,” said Christopher Lochhead. “Fear of rejection is something that stops many people in their tracks. It’s important to underscore that criticism is just part of the game. Legendary entrepreneurs and content creators should not try to appeal to everyone. If you have the courage to be different, to standout, having people who do not like your work is a sign you’re doing it right. It’s time for all creators to say, fuck the haters!”

The Business Case For Becoming A Category Creator In 2021 (And Why Most People Ignore It)

Originally published by Category Pirates ?☠️☠

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and fellow Category Pirate,

Category designers introduce the world to new ways of living, working and playing.

They are people and companies who move the world from the way it is, to the way they think it should be—often by solving a problem people didn’t know they had, or by reimagining a known problem and then creating the potential for a radically different solution. Most of all, they create (and subsequently capture) the exponential new value generated by an ecosystem of employees, customers, partners, investors, and communities.

TL;DR: category designers play the game differently, and experience outsized rewards as a result.

To make sure our Kool-Aid tasted as good as we thought it did, we recently conducted a set of studies to wrap our brains around the difference between Category Creators and other fast-growing, successful businesses.

We analyzed the Fortune 100 fast-growing companies list from 2009 to 2018.

Using our Category Design Scorecard (more on that coming), we found only 19 percent of the fast-growing companies were actually category creators. But stunningly, the category creators captured the vast majority of the growth: 51 percent of the prior three years cumulative revenue growth, and 80 percent of the prior three years market capitalization.

That’s not just differentiation.

That’s radical differentiation.

Companies that create new categories or successfully redesign existing categories are the ones that ultimately change the world AND create exponentially more value for both shareholders and the entire market in the process.

Now, if there’s data that supports our thesis that category design is the fastest, most effective way to grow, then why do so many companies insist on competing?

Fortune 500 companies have the hardest time understanding category design as a growth strategy.

They are conservative for a reason. They have “stuff” to conserve.

That “stuff” is everything from existing market share to quarterly company profits to investor relationships to balance sheet optics. In most large companies (and in many existing smaller companies as well), executives get paid to “Not f*ck things up.”

These incumbent companies are often themselves aging Category Kings. They were once the rebel-headed upstart pioneering new territory in the business landscape, but now, they are stuck defending the slow-moving, slow-growing category with which they’ve become synonymous. So much so, that despite incrementally growing profits year over year, many feel no urgency to change.

The unfortunate reality is that the fear of losing what ground they have today is greater than the exponential value that could be generated by embracing category innovation tomorrow. These companies live out their days bound (like hostages) to the tyranny of quarterly expectations, trying to convince themselves, their employees, and their shareholders there is still “a bit more juice left in the squeeze.”

Winning isn’t a destination—it’s a constant state of category design.

If history has taught us anything, it’s that successful companies of the past are rarely the ones that stay alive long enough to create the future.

There was a point in time when Xerox was one of the most innovative companies on the planet. In 1959, the Xerox 914 copier was seen as a breakthrough product because it didn’t require special paper and could print multiple copies per minute. Fortune called it, “The most successful product ever marketed in America.”

For decades, Xerox changed the business landscape—with Xerox machines in nearly every major office on the planet. And today, Xerox still does nearly $6 billion in annual revenue (2020).

Unfortunately, that’s a fraction of the $20 billion in revenue it was doing from 2011 to 2014.

Ask anyone in 2021 what they think of Xerox and they’ll probably say:

- “Is Xerox still alive?”

- “Oh man, I can’t remember the last time I used a copy machine.”

- “The world is going paperless. Xerox is going to die.”

And so on.

Nobody cares about Xerox anymore because Xerox—again, 40 years ago, one of the most legendary companies of all time—no longer dominates any category that matters.

It’s not that Xerox, the brand, has lost its flair. Xerox has a great brand.

It’s that the CATEGORY, wherein Xerox is / was Category King, no longer matters. It’s declining. It’s contracting. It’s drying up, like a raisin in the sun.

As digital storage products and paperless culture have grabbed hold, Xerox’s category has been redesigned—not by Xerox, but by new companies with a different vision of the future. As a result, the company is now securely fastened into a tailspin with revenues declining 35% year-over-year.

They don’t have a branding problem.

They have a category problem.

As a result, executives, shareholders, and employees are stuck in a game of defending what they once had (chasing market share) opposed to creating what could be. They know their time is limited, and so they are trying to squeeze as much “juice out of the lemon” before the company, and its entire category, goes to zero.

Which leads us to the morale of our story:

Legendary companies, and people with legendary careers, create new things. They don’t fight over old things.

To be blunt, if you don’t start, invest in, or work for a category creator or category-designing company, you are settling for a loser’s life. Consciously or unconsciously, you are saying, “I don’t want to be part of creating the future.”

(We are being brash and blunt to emphasize a sense of urgency.)

Now to be fair, most successful businesses are partially about monetizing the past and partially about inventing the future. The problem is getting the past-milking and future-creating mix right. Because the truth is:

- The past feels comfortable.

- The past creates an illusion of comfort.

- The past has gravitational pull.

As a result, business people want to be part of capitalizing on the past, and getting in while the getting is good.

This gravity is what sucks down Fortune 500 companies and startups. In the short term, attaching to an existing market category can seem advantageous. The rewards appear more likely guaranteed. And like most “conventional wisdom,” chasing the gravitational pull of the past tricks even the most seasoned executives, entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists into making the mistake of trying to build better, faster, cheaper, smarter versions of already proven products.

But let us tell you a quick story to accentuate our point:

Andy Rubin, creator of smartphone software Android, made this mistake.

And as a result, his company “Essential Products” went from being worth $1 billion in 2017 to bankrupt in 2020.

Maybe he prays at the “best product wins” alter too?

On the other hand, the original Android phone was different. And when Google purchased Android and gave it away, it became super different. But when Rubin left to start his new smartphone company Essential, he embraced a “Better Product” vs. Different Category strategy.

That category blunder cost his investors $330 million.

Category failures waste investors money, for sure. But the loss comes in two forms. Money lost and value wasted in unrealized category potential. If Rubin had designed a different product, company, and category, he might have created massive new value. All of that potential is lost now too.

It is our core belief that deep within each and every human being is an innate desire to create.

It just so happens the joy of creating often comes with outsized rewards.

In the beginning, and certainly along the way, category creators building a “different” future rarely seem like the safest bet when assessing surface-level metrics (such as: “the fastest growing companies of the year”).

But our research reveals that when assessing a company on five key areas related to their advancing foothold in a new or existing category, there are unquestionable signals as to whether or not that company will become “king/queen”—and capture two-thirds of that category’s economics as a result.

What are those five key areas, you ask?

Stay tuned…

Arrrrr,

Category Pirates

This article was originally created for the Category Pirates Newsletter. To subscribe to Christopher’s premium newsletter, visit Category Pirates.

All Press Is Good Press, Right?

I recently got invited to be featured in a publication that spotlight’s “influencers”.

If you know anything about me, you know, I believe most social media influencers are hustle pornstars, selling bullshit.

Assholes who want to be famous for the sake of being famous, selling courses to people they’ve duped into thinking, that being famous for the sake of being famous, is actually a worthy pursuit.

So I politely took a pass.

“All press is good press”.

I’ve heard this since I was a kid. And it is 1000% marketing bullshit.

One of my favorite expressions is, “position yourself or be positioned”.

Submitting to PR, that positions you in the wrong way, even when the exposure might seem positive, is a mistake.

I would have lost massive integrity points for submitting to being positioned as an “influencer”.

More importantly, I would disrespect myself for doing it.

So I didn’t.

To learn more about category creation/category design and marketing, subscribe to Category Pirates ?☠️ newsletter.