Silicon Valley Legend, Rick Bennett, Took Oracle From $15M In Revenue To Over $1B. Here’s How.

In Silicon Valley, Rick Bennett is a coveted secret weapon.

If you want to psychologically attack the competition with your marketing tactics, Rick is your guy (if you can get him). He won’t bother with hesitant clients. He doesn’t do boring, safe, or average. Hire somebody else for that.

Rick Bennet is the AC/DC of advertising and marketing. He found a format that rocks, does it extremely well, and sticks to it. Aside from always looking for new technology to test his messaging, he doesn’t change much—because he doesn’t need to.

He is also the mastermind behind Oracle’s genius ad strategy that skyrocketed the tech company’s growth in sales from $15 million to a staggering $1 billion between 1984 and 1990. With Rick’s permission, Salesforce later borrowed his Oracle strategy and achieved great success.

Today, he launches startups into the stratosphere through controversial, insanely effective guerilla warfare marketing strategies.

I actually worked with Rick early in my career as the chief marketing officer of a Silicon Valley startup. And the guerilla warfare marketing crash course he gave has stuck with me throughout my professional life.

Rick says what he does is “clinically incorrect.” Well, if that’s the case, I don’t want to be right. On the Follow Your Different podcast, Rick and I talked about how, while marketing has evolved in big ways over the last few decades, his bold approach has stood the test of time.

Lightning never strikes the same place twice.

Rick once placed a $15,000 ad in the Wall Street Journal for Linuxcare, a software company, that simply said, “Linus Torvalds for president.” Torvalds is the creator of the Linux operating system Linuxcare developed tools for. Shortly after the ad ran, Torvalds showed up at a tradeshow and spent hours signing copies of the newspaper at the company’s booth.

A simple, bold message with dynamite results. That’s the Rick Bennett formula, in a nutshell.

While he likes to stick to the script, he’s learned there’s a fine line. You can’t use the exact same strategy twice.

In an attempt to recreate the success of the Linuxcare ad, Rick ran a similar ad for Reachable, a Salesforce analytics platform, that read, “Marc Benioff for president.” Benioff, of course, is the founder and CEO of Salesforce. At a subsequent Salesforce conference, Benioff had to fend off hordes of media members asking about his potential (non-existent, of course) presidential campaign, which he didn’t appreciate.

That was Rick’s last ad with Reachable.

The secrets behind guerrilla warfare marketing.

Rick plays hardball.

One of his main goals is to make the competition “go crazy” and “generate mistakes.”

One such example of succeeding in this pursuit is an ad he came up with for Salesforce that said, “I will not give my lunch money to Siebel.” The aftermath, for Siebel, was catastrophic. Their executives apparently called up every publication that published the ad and swore to never advertise with them again. Siebel never recovered.

While working with Oracle, Rick destroyed a competitor’s campaign with just nine words. Digital Equipment Corporation was about to launch Rdb, and include it for free with every VAX computer purchase. Oracle ran an ad saying, “You wouldn’t want Rdb even if it were free.”

Digital Equipment Corporation went crazy and ended up selling Rdb to Oracle in an incredible turn of events.

ASK Technology also suffered from going to war with Rick. As a genius preemptive strike, Oracle launched the ad “WE KICK ASK.” ASK Technology responded by promising products they could not deliver. As a result, ASK Technology ladies and gentlemen no longer exists and Oracle successfully conquered a new market.

The master sensei of ad copy and writing headlines.

I asked Rick what advice he would give to a young person interested in becoming a master of writing ad copy. Here’s what he said:

- First, find a product to sell. It doesn’t have to be your own—maybe your brother-in-law invented a new device.

- Second, test out messaging on social media. Test away, don’t be shy. Throw 20 different ads into the social media universe. Give a ridiculous ad copy a shot and see how it performs. There’s little risk early on.

- Third, find a strategy that works and run with it. Do something legendary. Become the Howard Hughes of your own dreams.

Rick is very consistent —straightforward. Hard-hitting. No nonsense.

His approach isn’t for everyone. It takes a particularly bold CEO to roll with Rick. And he’s dealt with a number of hesitant CEOs.

So how does he convince an on-the-fence client?

He reminds them you have to take chances to win. Especially when your back is against the wall and you have nothing to lose. Your board of directors could fire you tomorrow anyway. Why not take that chance and bet all your chips on a bold marketing strategy?

To listen to the full podcast with Rick, click here to Follow Your Different.

Snow Leopard: Why Legendary Writers Create A Category Of One

Most writers spend their entire lives trying to become “great.”

But what does being a great writer mean?

- Is it when you go viral, and accumulate over a million views on something you’ve written?

- Is it when a major publisher gives you a book deal?

- Is it when a magazine says you’re “talented?”

- Is it when your parents (and all their friends) applaud your work?

At what point is a great writer, “great?”

Let’s skip to the answer: Great is relative.

The word “Great” implies competition.

In order for you to be “great,” that means someone else has to be “not-great.” Which means the entire goal of becoming “great” is a never-ending cycle of comparing yourself to anyone and everyone around you, and then trying to figure out how you can “out-great” them—until the next person comes along, and who you have to “out-great” changes, and so on.

As ridiculous as this sounds, this is how most writers spend their entire lives & careers.

Comparing themselves to others in search of “greatness.”

Forever stuck in a game of competition.

Legendary writers, the ones who stand the test of time, do none of this.

Who is a better writer: David Ogilvy or Charles Bukowski? Most sales copywriters rush to say the former and don’t even know who the latter is. And most people in the literary world rush to say the latter and don’t even know who the former is.

Who is a better writer: Malcolm Gladwell or James Patterson? Most people rush to say the former, but the latter has sold 1000x more books. So how are we defining “great?”

If you look closely, what you’ll notice is that the most influential writers of all time are impossible to compare. They aren’t “regular leopards” (regular writers, all competing for who is a better novelist, who is a better journalist, who is a better copywriter, etc.). They are Snow Leopards — and they stand alone.

The big question, of course, is how?

Snow Leopard: How Legendary Writers Create A Category Of One

For example, what is the author Ryan Holiday’s category?

Ask 500 people this question, and all 500 will say the exact same word:

- Stoicism

- Stoicism

- Stoicism

- Stoicism

- Stoicism

- Stoicism

- Stoicism

- Stoicism

We as human beings are not taught to think this way. Instead, all growing up, we’re taught to choose an existing industry and then “compete” our way up the ladder. But this is not what legendary writers, creators, and even entrepreneurs do. Instead, they become known for a niche they own. Why has Ryan Holiday sold so many books? Because it’s very easy for readers to a) understand WHAT he’s writing about, b) understand WHO it’s for, c) understand WHY it matters, and d) talk about it.

So how fast does word-of-mouth marketing spread when everyone uses the same word to describe who you are and what you write about?

The answer is: very fast.

Your goal as a writer (or creator, or entrepreneur) is not to become “the best” in an existing category.

Your goal is to create your OWN category.

And then give readers the language you want them to use to describe who you are, what you write about, and why it matters.

Snow Leopard by Category Pirates is the first “writing” book ever written through a Category Design lens.

Category Pirates—composed of myself, 3x CMO & chart-topping podcaster, Christopher Lochhead, and billion-dollar growth strategist, Eddie Yoon—is the authority on Category Creation & Category Design.

And each week, we publish a mini-book (5,000–10,000 words) on these subjects, educating people on the importance of differentiating themselves in their work and careers—and how exactly to do that.

But we just published a book specifically for writers & creators, called Snow Leopard, digging into how writers and communicators specifically should think about “niching down.”

Including:

- The benefits of creating Obvious & Non-Obvious content

- The power of having a unique & highly differentiated POV

- How to use “languaging” to Name & Claim new ideas (and make them “stick”)

- Digital business models for writers & creators, and how to monetize your work multiple times

- Why the content marketing industry is becoming painfully saturated (and the opportunity this creates for writers willing to “think differently”)

- And the Content Pyramid, and how you can climb your way up from being a consumer, to a curator, to a Creator.

We also conducted the world’s first non-fiction study of best-selling business books, reverse-engineering what made them successful. From there, we created our own framework you can use to ensure the book(s) you write have the most Reach & Resonance potential possible.

If you are not making 6 figures as a writer, you don’t have a writing problem.

You have a differentiation problem.

You have a languaging problem.

You have a category problem.

To fix that, give Snow Leopard a read. You can grab a copy here on Amazon (print & eBook).

This is the book I wish one of my Creative Writing professors had given me 10 years ago.

(It would have saved me a lot of time and wasted effort.)

How To Make Money In A Recession: 5 Steps To Create Demand For Your Product, Service, Or Platform

Recessions are the worst time to fight for demand. And recessions are a great time to create demand.

Originally published by Category Pirates🏴☠️

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and Category Pirate,

We are in a recession.

(Not officially, but it is not looking good.)

Stocks are down. Startup valuations have plummeted. Bitcoin and Ethereum have lost more than 50% of their total value since their respective highs back in November, 2021. And sentiment around Silicon Valley is that the next 12-18 months are going to be challenging for companies looking to raise money.

But where there is chaos, there is opportunity.

Approximately 10% of companies get stronger in downturns. And you can’t be in the 10% unless you do some serious thinking.

Through the category lens, downturns are simple to understand—and have a clear path to navigate. When times get tough, businesses, governments, households, and individuals all do the same thing: they create two lists.

- “Must Haves”

- “Nice To Haves”

Then they start cutting the “Nice To Haves” to lower costs—as a direct response to their revenue / income / buying power shrinking.

Which means the seminal question is: what makes people put some categories/brands/products on the “Must Have” list versus the “Nice To Have” list?

Perceived value.

(Everything we value, we’ve been taught to value.)

The difference between a dumb idea and a great one, or the difference between useful products and useless ones is the perception we have based on what we have been taught. (Don’t forget: pet rocks used to be in demand.)

The trick is to get your product/service/platform on the “Must Have” list, and to be as high up on the list as possible. Because the higher the category is on the hierarchy of perceived value in the consumer’s mind, the greater the likelihood they will keep buying from you.

Which is why savvy leaders market the category in downturns.

Because people make their lists by category first, and brand second.

(“Alright Tom, we are paying for 3 different streaming (category) services right now. Which one (brand) don’t we need?”)

Elon Musk was a guest on the All In podcast and summarized the net-positive effects of recessions well:

“Recessions are not necessarily a bad thing. I’ve been through a few of them. What tends to happen, if you have a boom that goes on for too long, you get misallocation of capital. It starts raining money on fools, basically. Any dumb thing gets money. At some point, it gets out of control… and the bullshit companies go bankrupt and the ones that are building useful products are prosperous.”

When most people hear the word “recession,” they imagine the housing crisis of 2008 or the dot-com bubble in the late 90s—and all of the businesses that went under as a result.

But what doesn’t get talked about enough are the incredible companies that emerged out of these challenging times as well. Google and Amazon both came out of the dot-com bubble in the 90s (as did hundreds of other world-changing companies). And Uber, Spotify, Airbnb, Square, and dozens of other next-gen technology companies were founded between 2006 and 2009, right in the middle of the greatest financial crisis to ever threaten America.

Recessions are pressure-cookers that rid the system of businesses failing to live up to the value they are promising society.

Here’s how it happens:

The Company Downturn Cycle Of Doom

Step 1: Recession hits.

Stocks crash. Capital dries up. Investors stop playing as many hands and start sitting out of deals. Consumers tighten their belts and begin to examine their spending habits. The music comes to a halt and everyone in the room stops dancing.

Step 2: Demand falls.

The result of all this “tightening” is that consumers spend less. Suddenly, that vacation you were planning (and that Airbnb you were looking at) goes from a “need” to a “want.” And not just a “want,” but a “want” you have to work harder and harder to rationalize to yourself. Companies (like Airbnb, for example), immediately feel this change in temperature. Bookings go down. Revenues fall. Inventory builds up at large retailers like Target and Walmart (43% and 32% year over year respectively) that has historically led to both big chains missing revenue expectations. Not by a lot—just enough to make everyone pause.

Step 3: Companies start playing “The Better Game”—hard.

Demand has started falling, which means companies that have employees to pay and investors to keep happy need to work twice as hard to earn the same amount of money they did a few months prior. Their entire strategy becomes to “catch” demand. As a result, they fall into The Better Trap, which is often “my deal and discount is better than everyone else’s.” These companies believe there is a fixed number of people willing to spend money in this current environment, and they become myopic about convincing those select few customers to shop with them (opposed to one of their competitors—who are furiously doing the exact same thing).

Step 4: Customer acquisition cost goes up.

Before the recession, customer acquisition costs were $X. Now, they are 2x, or 3x, or 5x times higher. For every dollar you used to spend acquiring a new customer, you now have to spend two. This chops your profit margins down a size, which accelerates the existential threat to your company.

Some tech startups burn half of their venture investors’ money on demand capture with Google and Facebook. And executives who have already dug themselves a deep competition hole drive CAC through the roof as they try desperately to catch the falling demand knife in downturns.

Step 5: Cash flow goes in the wrong direction.

Lowered revenue and profit margins lead to lower cash flow.

Which means now you’re spending more to make less cash.

But it’s not just you. It’s you, plus all your competitors, plus all the other tangentially related companies in your industry, plus all the other companies that have cash flow going in the wrong direction. As a result, cost of capital increases as valuations/market caps go down, while debt and credit financing go up with interest rates.

Until eventually, your company runs out of money.

Recessions are the worst time to fight for demand. And recessions are a great time to create demand.

The truth is, you never want to be in a position where you have to “fight” for demand. (We call this The Better Trap.)

But in a tightened environment, fighting for demand is the equivalent of trying to run a marathon while simultaneously holding your breath. Running is taxing. And depriving yourself of what you need to breathe is also taxing. Both at the same time is the worst idea you could have.

Instead, especially in a recession, the people who know how to create demand become most in demand.

- They create what is suddenly urgent, important, and most useful in the world.

- They remove themselves from “comparison” conversations and educate customers on “different” problems, solutions, and outcomes (that they likely haven’t considered before).

- They allow “competitive” companies to waste their resources fighting against each other, and leverage this unique period of time to create net-new opportunities for themselves and the customers they want to serve.

- They force a choice, not a comparison.

- They elevate the value of what they do (at the level category level, not the product/service level).

Here’s how:

Your Money-Making Recession Strategy

Step 1: Create High-Value Non-Obvious Insights

We wrote about how to do this in our mini-book, The Art of Fresh Thinking.

Non-Obvious insights are what unlock exponential value that did not exist before (that’s what makes them Non-Obvious!). How you find them is by auditing today’s newest, hottest, most popular solutions—because today’s solutions create tomorrow’s problems, and tomorrow’s problems create category opportunities.

By auditing the solutions society values most heavily today, what you’re going to find are emerging (potential) categories with strong tailwinds behind them. And solving tomorrow’s problems before anyone else is just another way of saying “solving Non-Obvious problems.”

And these problems are Non-Obvious because the world hasn’t realized which way the wind is blowing yet (which means you can be the first to frame tomorrow’s problems, provide a solution, and own the category of outcome).

For example: let’s pick up the story from the Downturn Cycle of Doom. You want to build up cash reserves, but both the equity and debt capital markets are unattractive. What can you do?

Look within your value chain by turning to your Superconsumers or suppliers.

Supers are the most recession proof part of the economy because they have certainty of demand that lasts decades longer than any economic cycle. They are also the savviest consumers in the category, so make them an offer they can’t refuse. Create a bulk bundle that gives them a great volume discount. Subscriptionize your product or service in a longer term deal that gives you cash up front for services in the future. (Cash now is always better than cash later.)

But there is another growth secret about Supers:

If you are radically different and deliver transformational outcomes, they will never let you go.

The very last Blackberry users held on ‘til January 4th 2022 until the company pulled the plug. They were Supers. These Supers hold on because they “need” you. The category is part of their identity. It’s built into a part of their work and broader life. They have invested money, time, and in some cases part of their spirit into the category and the category leader’s brand and offerings. Another great example: during the early 2000s Microsoft stopped innovating for about a decade. They took ten years off. They did very little product, technology, and category innovation… and ended up missing the entire Cloud category.) You’d think they would have crumbled, and competition would obviously overtake Microsoft with clearly “better” products.

So why is Microsoft still one of the most successful and valuable companies in the world?

Supers wouldn’t (couldn’t) let them go! Microsoft had approx 90,000 employees, 640,000 partners, and a billion users in 2010. (All with exorbitant switching costs and huge investments with Microsoft). So—driven by the trendsetting Supers—the category held on, even as Microsoft looked like it was becoming Wang Laboratories. Then, once they started to innovate and create and (re)design categories under the leadership of Satya Nadella, they executed one of the greatest turnarounds in history.

Said a little differently: Pirate Eddie is an electric vehicle/Tesla Super. Pirate Christopher, on the other hand, refuses to buy one. He loves American Muscle cars—and has a deep personal relationship with his 2014, 662 horsepower Shelby Cobra Mustang. (Category first, brand second.) And no amount of marketing will ever get Pirate Christopher to buy a Tesla, or Pirate Eddie to buy a Shelby Cobra Mustang. Instead, marketing dollars would be better spent educating a Super like Pirate Eddie on why he should pre-order the new Tesla Cybertruck, or a Super like Pirate Christopher on why he should add a handful of vintage, collectable Mustang parts to his classic Shelby Cobra.

Instead of trying to market to new customers, consider how you can increase cash flow by getting your Supers to open up their wallets and buy more of what they already (clearly) love.

Here’s another example:

Guitar players universally respect (and many “love”) the legendary Gibson. But after expanding recklessly into adjacent categories, with a competitive/comparison mindset, the company collapsed into bankruptcy. Old management out. Then, new CEO JC Curleigh declared a “true to roots” initiative. Translation: “We’re going to focus on our Supers in our core categories with our most legendary products and brands.” The company, after very strong complaints from Supers, also stopped attacking smaller knock-off competitors and created an “Authorized Partnership Program” with boutique guitar makers.

This is a legendary example of a strategy that expands the category potential while diverting attention and resources from competing to monetizing collaboration at the same time. And it works for companies of all sizes. Satya Nadella and Microsoft did the same.

“So it is notable that Nadella has put Microsoft back at the top of the tech heap without attracting the resentment and anxiety provoked by some other tech leaders—or, for that matter, Microsoft’s own former self. The software company was once considered to be the model of the corporate bully, using its dominance over PC software to hold sway over the tech world.” —L.A. Times.

But big suppliers also have an interest in making sure their partners whom they sell through survive a downturn. Sometimes the same company or person can be both Superconsumer and supplier.

The most legendary example of this is when Microsoft invested $150 million into Apple, effectively saving Apple from bankruptcy in 1997. In exchange, Microsoft provided Office to Macs and Apple made Internet Explorer the default browser which helped Microsoft appear less monopolistic as it was negotiating a lawsuit with the government.

“In a way, you could say it might have been the craziest thing we ever did. But, you know, they’ve taken the foundation of great innovation, some cash, and they’ve turned it into the most valuable company in the world.” —Steve Ballmer, former CEO of Microsoft in 2015.

So next time you look at your iPhone, iPad, or Apple Watch, make sure you say thank you to Steve… Ballmer. We’d bet you the Brooklyn Bridge that it took a lot of Non-Obvious thinking from both Mr. Ballmer and Mr. Gates before getting that buck fifty to Jobs.

Today both Apple and Microsoft are two of the most valuable companies in the world with multi-trillion dollar market caps. And Microsoft made around $550 million from its Apple lifeline—a 260% gain in just six years.

These are the kinds of Non-Obvious insights much of the business world tends to avoid looking for and thinking hard about (“Why would we ever help our competition?!”).

But these Non-Obvious insights are often what lead to incredible opportunities and abundance for all.

Step 2: Convert Your Non-Obvious Insights Into Intellectual Capital

Peter Drucker was the one who named & claimed the idea of being a “knowledge worker” as someone who earns with his or her mind, not their muscles.

But he first coined this term back in 1959, and the world has changed dramatically since then. In a world where information is a commodity (where a 7-year-old can ask their smartphone how many home runs Babe Ruth hit, or how many stars there are in our galaxy), having “knowledge” today isn’t nearly as valuable as it used to be. When Drucker invented the term “knowledge worker,” the game of business and life was to acquire knowledge and then apply knowledge—a doctor gets paid per hour to apply their knowledge of medicine, a lawyer gets paid per hour to apply their knowledge of the law, etc.

Today, the game is to acquire knowledge, leverage Non-Obvious insights to build upon that knowledge, and create net-new Intellectual Capital. This is knowledge that did not exist before you took the time to draw a conclusion between two or more disparate, maybe even conflicting ideas and/or data points.

And how do you find these Non-Obvious insights?

Again: talk to your Supers!

Most companies launch innovations after months or even years of prep work behind the scenes—only to let their big, grand reveal fall on deaf ears.

But savvy companies understand that Superconsumers can be a source of precious real-time feedback in a soft launch that dramatically increases the odds of success. Tesla is doing this right now with its full self-driving beta, releasing it to only 100,000 users who will use it safely and provide massive amounts of data to optimize and improve the feature before its full rollout. Or, another example: Safeway (the supermarket chain) used to test its private label innovations in just a few stores, get feedback, and then optimize and roll them out nationally afterwards. Michael Fox, the former CMO of Consumer Brands at Safeway and now CEO of California Olive Ranch noted that their innovation success rates were much higher than they were back in his Frito Lay days where he had significantly more resources.

But Supers don’t have to just be your customers.

Supers among your employees are some of the best sources of Non-Obvious insights. When Steve Hughes was at Tropicana, he was walking the factory floor when he saw some of the workers enjoying a glass of orange juice after their shift. Right then, he noticed something Non-Obvious… they were putting the pulp that the factory had just painstakingly removed back into the glass. He asked them why and they said it tasted even more like fresh squeezed orange juice. Steve took that Non-Obvious insight and led the creation of Tropicana Grovestand with pulp, which became a billion dollar product.

The takeaway here is: don’t think of innovation as something that has to happen in a vacuum (we know too many founders, business owners, executives, and investors who need to feel like “they” were the ones who came up with the company’s big, game-changing idea).

Instead, talk to your Supers—customers, clients, and employees. Ask them questions. Let them tell you what their biggest pain points are, and their wants and needs and hopes and dreams for the category. See what they are doing and join in.

Supers will usually tell you the right answer (or at least point you in the right direction) if you take the time to listen.

Step 3: Convert Your Intellectual Capital Into Digital Products/ Services/ Businesses

When you create Intellectual Capital, you have something no one else does.

Which means you no longer have to “fight” for demand.

You can create it.

Even in a tightened economic environment, you have the opportunity to educate people on your new, different, Non-Obvious insights. During times of crisis or change people are naturally more open to different ideas. They are very aware they are living in an obviously different world (think about the COVID-19 pandemic), which challenges their historical assumptions, which opens the aperture of their minds and makes them more willing than normal to consider a Non-Obvious, different future (and all the new categories that can or should exist in that new and different future).

Non-Obvious insights are significantly more valuable than Obvious, commodity insights (things the world has already priced, and already determined whether they want or do not want), which means you can charge more for them—look at you thriving in a downturn! In addition, when you can plug your Intellectual Capital into frictionless, infinitely scalable, digital platforms and products, you can also monetize your “knowledge” in a way traditional knowledge workers cannot (that’s the beauty of software, newsletters, websites, podcasts, and content). A doctor only gets paid when she or he performs a surgery. And a lawyer only gets paid when she or he accumulates billable hours. But these rules are not true for a SaaS company or any form of digital content/creation. These are “build once, scale-massively-at insane-margins” businesses that go ching-ching-chitty-ching-ching (as in an old-school cash register).

Getting paid in the future for Non-Obvious insights you created/published in the past is Intellectual Capital.

We want to be clear here though: Intellectual Capital isn’t just “theory” for professional services firms, but is a strategic asset that turns into an economic asset. For Intellectual Capital to be given a value or price, it needs a market where buyers and sellers agree. Which means you have to either plug your Intellectual Capital into a marketplace that connects Superconsumers and suppliers that maximizes monetization and/or mindshare, or create one yourself.

For example, a few years after nearly avoiding bankruptcy, Apple launched the iPod and iTunes store in 2001. iTunes was the Intellectual Capital pivot from Apple being a product and software manufacturer to an Intellectual Capital based ecosystem. Both iTunes and the App store are an Intellectual Capital marketplace platform where Superconsumers and suppliers can meet and transact, all while Apple both takes a cut but also ensures its relevance as the center of gravity in the category.

Now, obviously not every business is going to go create a multibillion-dollar next-gen marketplace—that’s not what we’re saying. Digital content/products is the lowest-barrier-to-entry way to scale your Non-Obvious thinking (and Intellectual Capital) in a way that does not require you to show up to the office and perform surgeries and/or rack up billable hours.

It takes us approximately 6-10 hours per week to write each Category Pirates mini-book. And this amount of time, energy, and effort remains constant whether 6 people, or 600 people, or 6,000 people, or 6 million people read it—allowing our earnings as writers and Intellectual Capitalists to be “infinitely scalable.” Which is the opposite of even the most prestigious legacy “knowledge work” where income scales linearly with time, energy, and effort.

(Pirate Chrstopher’s podcasts have been downloaded in 190 countries. And while he’s done a lot of traveling, he’s never been to many of the places his work has been downloaded in.)

Even the highest-paid knowledge workers today are beginning to wake up to the fact that life is much better when you’re an Intellectual Capitalist. (Which is why 86% of Native Digitals want to be creators, not lawyers.)

Step 4: Design New Categories For New Digital Products/ Services/ Businesses

Once you build the skill of being able to spot and create Non-Obvious insights and turn those insights into unique, differentiated, one-of-a-kind Intellectual Capital, you can create net-new categories in the world.

Over and over again.

Again: the people who know how to create demand become most in demand.

Apple used its early success with iTunes to build more marketplace platforms like the App Store where consumers could not only transact, but also create and commercialize. And Whole Foods has its Local and Emerging Accelerator Program (LEAP) to incubate new brands and categories to be sold in its stores.

Jeff Bezos, who has recently let loose on Twitter, tweeted a cover of a 2006 BusinessWeek magazine calling his software bet “risky.” The bet was predicated on the Non-Obvious insight that Amazon’s B2C growth required more computing power, but that building Amazon’s cloud capabilities could also be remonetized as a B2B service. That software bet became AWS, which generated $62 billion in revenue last year (and is one the greatest B2B tech companies ever).

The big idea here is to consider what “costs” you can turn into revenue-generating machines. Instead of just assuming every business needs to spend money on marketing, or fulfillment, or distribution, or customer service, how can you create new categories, products, and services that turn those cost centers into revenue generators?

For example, here’s one way we have done this with Category Pirates:

You give us our book advance, not a big publisher.

When we originally started Category Pirates, we just wanted to write a book. And most people who want to write a book consider the legacy business model for “writing books”: pitch a publisher, get an advance, give up 85%+ ownership in the book, and publish it 2 years later (and we had multiple publishers interested… just sayin’). The “cost” here, however, is that even though you get paid some money up-front, you have to give up majority long-term ownership.

Instead, we flipped the model on its head and decided not to write a book (first), but to write our book “in public” via a paid newsletter.

This allowed us to…

- Build an audience while we explored new material—opposed to building an audience in the 9th hour, right before the book’s launch.

- Charge per month or per year opposed to “for one book”—unlocking more digestible, “read at your own pace” content for readers and more financial upside for us (most authors charge $20 per book, we charge $20 per month or $200 per year. That’s a 10x difference!).

- Have readers “pay our advance” to write the book. Instead of a publisher giving us $50,000 or even $100,000 up-front and then taking 85%+ ownership, readers pay us $20 per month or $200 per year, giving us some cash “now” and essentially paying us to write (which means we no longer have to pay the cost of giving up 85%+ ownership).

- Our Super readers buy both: the newsletter and the book. When we published our first two books last year (2021), The Category Design Toolkit and A Marketer’s Guide To Category Design, we learned that our Superconsumers didn’t want one or the other (the newsletter content or the big book content). They wanted copies of both! (Remember: Supers buy more, more often.)

These types of opportunities exist everywhere. And together with your Supers, you should be able to learn what “cost centers” you can turn into revenue generating win-win scenarios for you and your most enthusiastic Intellectual Capital consumers.

Step 5: Market Your New & Different Category—And Win

Businesses that thrive in recessions have no competition.

They avoid The Company Downturn Cycle Of Doom completely. They do not waste their time trying to “catch” what little existing demand is left for products or services the world may have concluded (in an instant) no longer serve them. Instead, these Category Creators use their time, energy, and resources to create net-new demand by solving tomorrow’s problems, today.

And as a result, they emerge victorious.

- Apple will be increasingly known as a subscription and marketplace company versus a hardware company.

- Whole Foods may increasingly be known as a venture company (incubating and/or investing in new products) as much as it is a grocer.

- Amazon will be increasingly known as a B2B services and technology company as it is a B2C e-commerce retailer.

Now is no time to work on the incremental.

Repeat this over and over again to yourself, like a mantra.

When the world is thrown off-balance, now is not the time to batten down the hatches and fight over a limited number of resources. That’s not what the world needs, and that’s not what you need in order to thrive.

Instead, this is your chance to create what has not been created yet. As we said at the beginning of this mini-book, some of the world’s most legendary companies were born out of downturns. This is not an expectation for you to go create the next Google or Uber, but should serve as a reminder and Rally Cry for your full potential.

Now is no time to work on the incremental.

Now is no time to work on the incremental.

Arrrrrrr,

Category Pirates

PS. – When the going gets tough, the tough design new categories.

Why (Positional) Power Is NOT The Greatest Power: The Legendary Lesson Madeleine Albright Taught Me

As a door opened, a soft “aahh” came over the 25 executives waiting. Madam Secretary had arrived.

(Everyone was there for her, but it was still surprising to actually see her)

The first female US Secretary of State was radiant in red. (Featuring one of her famous brooches)

Warm, welcoming, laughing and listening, she took time to meet everyone.

She shook my hand confidently (all four-feet-ten inches of her), looked me in the eye and told me she was glad to meet me.

Madam Secretary was that rare person who treated you like she’d known you for years. She was humble. The way she listened made you feel heard. Radically unimpressed with herself. 1000% focused on you.

We hired Madam Secretary to keynote our customer conference and I was interviewing her in-front of about 5,000 that morning.

As we prepared, I was struck by the fact that she once wielded more power than (almost) any person on earth.

As US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright could literally get a meeting with anyone. (Think about that)

The most powerful people would stop, listen to her every word and consider her every idea. With urgent attention.

Madam Secretary had gargantuan (positional) power. The exact kind of power (most) people seek in politics and business.

She could make people do shit.

Madam Secretary walked out to a standing ovation.

(no one made them)

5000 people hung on her every word.

(no one made them)

When she was done another standing ovation.

(no one made them)

Then I got it.

Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright had achieved something greater than (positional) power.

Real power. Personal power. The power to make a difference with your presence and participation alone. This was her “only” power now.

- Reputation

- Relationships

- Results

She could no longer “make” anyone do anything.

She was one of the toughest things you can be.

A “former”

- Former famous

- Former important

- Former (position) of power

Most “formers” fade out fast.

Many believe that power is something given, granted via an external source. (a title, resources, a budget, a team, etc)

And when your position goes, your power goes with it.

(Right?)

Not so fast. It turns out, NOT needing (positional) power is the greatest power of all. Power comes from within, NOT the positions we hold. It’s something we “earn” every day, not something we’re “given” once.

- Reputation

- Relationships

- Results

Today I have zero positional power. And I experience more joy and creativity, while making a bigger difference, than I ever did before.

Madeleine Albright taught me:

You can “make people” do something or “inspire people” to do something,

and those two things are not the same thing.

Bless you Madam Secretary,

Christopher Lochhead

Personal Branding In 2022: Three Considerations

(This is an excerpt from Category Pirates Mini-eBook, “The “Me” Disease: Why Personal Branding Is A Lie”

In 1997, entrepreneur, acclaimed author and founder of Skunkworks, Inc., Tom Peters, wrote a column for FastCompany’s print magazine.

The title of the article was, “The Brand Called You.”

This may very well be the first mention of “personal branding,” as Peters explains we now live (starting in the late ’90s) in a world of brands:

“That cross-trainer you’re wearing — one look at the distinctive swoosh on the side tells everyone who’s got you branded. That coffee travel mug you’re carrying — ah, you’re a Starbucks woman! Your T-shirt with the distinctive Champion ‘C’ on the sleeve, the blue jeans with the prominent Levi’s rivets, the watch with the hey-this-certifies-I-made-it icon on the face, your fountain pen with the maker’s symbol crafted into the end… You’re branded, branded, branded, branded.”

The solution?

According to Peters, the answer was to fight branding with branding; to stand out in a sea of brands with a brand of your own; to scream, shout, and proclaim yourself to be heard irrespective of message; shouting as both the means and the end and, well, let’s look where that’s gotten us 25 years later.

1) Personal Branding Today

A quick search on Instagram for the term “personal branding” yields 1.7 million search results.

Within that search you will find an army of personal branding experts, coaches, “influencers” and agencies, all determined to help you be bigger and better and louder than you were yesterday. In fact, personal branding has become so widespread there are even personal branding experts and agencies who specialize in not just “personal branding” (that’s so yesterday) but “authentic” personal branding. (Have you ever noticed that the people who overuse the word “authentic” are often the least authentic people?) As if, within the category of you being you bigger and better than everyone else, there is a truthful and honest way of being “you,” which is different from the inauthentic way of being you, at scale, on the Internet.

There’s just one irony, and it’s a big one.

If Tom Peters believed, in almost Nostradamus-like fashion, that personal branding would become as important to our society as almond milk, athleisure clothing, and working from home, then how come the very people carrying the flag and rallying the troops in the name of differentiation suck at differentiating themselves?

Here’s a case-in-point example.

“You are going to learn all the essentials leaders need to develop but don’t take the time to do. You will learn how to build a month by month plan, and build your personal brand with intentionality, authenticity, and results. The way you cut through the noise today is with a crystal clear brand story that rallies, galvanizes, and inspires the masses.”

Can you name who said this?

If the answer that comes to mind is, “No, that literally sounds like every single person preaching personal branding advice on Instagram or LinkedIn,” you’re right. Because that’s not the message of one person, known for a category or niche they own. That’s the message of Tom Peters, way back from 1997, copy/pasted by 1.7 million people who proclaim themselves to be “personal branding experts.”

There’s just one irony, and it’s a big one.

If Tom Peters believed, in almost Nostradamus-like fashion, that personal branding would become as important to our society as almond milk, athleisure clothing, and working from home, then how come the very people carrying the flag and rallying the troops in the name of differentiation suck at differentiating themselves?

The same way companies fell for The Big Brand Lie, good-hearted, well-intentioned human beings fell for The Big Personal Branding Lie.

And it has become a pandemic.

A Brief History Of Personal Branding

Back in 2012, when Pirate Cole (Co-Creator of Category Pirates) was just a young swashbuckler fresh out of college, he started working as an entry-level copywriter at an advertising agency downtown Chicago.

2012 was an interesting year for advertising and marketing. It was the year Instagram had reached the masses and been acquired by Facebook for $1 billion, which for the first time moved social media from people’s desktop computers into their pockets. Suddenly, social media wasn’t that thing you interacted with after a social event (uploading photos from last night’s party to Facebook). Social media was something you interacted with during a social event — and eventually, any event — through your phone. (And then social media became the main reason for having an event or experience….”If it’s not on Insta, then it didn’t happen…LOL.”)

As a result, everything (in the entire world) became “content”:

- Eggs for breakfast? Content.

- Out for lunch? Content.

- Unique architecture of a building down the street? Content.

- You, looking at yourself in the mirror? Content.

- Cats? Content.

The year was capped off with the “official launch” of Vine, a short-form video app that allowed users to create and share 6-second videos. The app had been originally soft-launched in June, 2012, before being acquired by Twitter just 4 months later (after seeing such rampant early user growth). The app, despite growing to more than 200 million users by the end of 2015 and being shut down a year later (2016), would go on to shape a handful of massively influential online trends. For example, Vine was the first time social media transformed from text and photos into short-form videos (and was the first time Facebook/Instagram blatantly copied another app’s functionality). And Vine gave rise to an entire cohort of social media influencers that would go on to dominate just about every other social platform, including: King Batch, Logan Paul, Jake Paul, Amanda Cerny, to name a few. These “influencers” wrote the playbook for how to build massive audiences and then leverage those audiences into five, six, and even seven-figure brand advertising deals.

Pirate Cole remembers this time well because, as a 23-year-old and the youngest employee at the digital agency where he worked, Pirate Cole built the company’s “influencer” department, helping national brands utilize professional mobile-first photography and short-form social video to deploy social media campaigns. And a few years later, in 2016, right before leaving the agency to become an entrepreneur, he launched the company’s personal branding department — something very few advertising and marketing agencies even had on their radars.

It was between this window of time, 2012 to 2016, that terms like “influencer marketing,” “personal branding,” and “vlogging” started to go mainstream. In 2014, wine entrepreneur turned advertising executive, Gary Vaynerchuk, launched his YouTube series, #AskGaryVee, and just 4 episodes in, he began preaching the importance of personal branding (this was the very beginning of Gary Vee-D… a digital transmitted disease). A year later, Tai Lopez’s infamous ad, “Here in my garage,” went viral, igniting an entire generation of “I-will-reach-you-how-to-be-rich” online gurus standing in front of lamborghinis and whiteboards explaining some simple 3-step process to financial freedom.

Now, back then, much in the same way companies talk about “digital transformation” today, this idea of “putting yourself out there on the Internet” was a powerful differentiator. If 99.8% of people exclusively operated in the analog world, and you were courageous enough to turn on the camera and share what you knew, at scale in the digital world, that was akin to using email instead of sending physical mail — or today, minting digital art on the blockchain opposed to selling physical art in a showroom. The simple fact that you were using technology and being a “creator,” not just a consumer of social media, meant you were part of the top 1%.

But the Gary Vaynerchuk’s and Tai Lopez’s of the world took things one step further: it wasn’t enough to just “put yourself out there.” You had to put yourself out there relentlessly (or, in the words of another personal branding hustle pornstar, Grant Cardone, “Be obsessed or be average”). And millions drank the Kool-Aid. Today, you can’t go anywhere on the Internet without seeing the Gary Vee-D “how to turn 1 keynote speech into 30+ pieces of content” model being deployed by everyone from podcast hosts to life coaches to nutritionists to CEOs of 8, 9, even 10-figure businesses.

In less than 20 years, Tom Peters’ idea of being a Brand Called You had mutated with mobile phones and social media to create a generation-defining aspiration and obsession: “Pay attention to me, everywhere, all the time.”

2) The “Me” Disease

A recent study revealed that 75% of children ages 6 to 17 want to become YouTubers when they grow up.

Read that ? sentence again.

For context, 13% of children surveyed said they wanted to become a doctor or nurse, and just 6% said they wanted to become a lawyer.

We now live in a digital world where the most desirable thing you can be is known on the Internet. For what….exactly? That’s less important. “Let’s just get famous for the sake of being famous and then we’ll do something with it later!”

86% of young Americans want to be influencers.

Read that ? sentence again.

Today, the goal for many is to be known, and to be known by lots of people — because once you have people’s attention, then you can decide what to do with it (aka: make money). So, how do you get people’s attention?

Here’s the Starter Kit:

- Post pictures and videos of you in front of cars, boats, houses, and nice things.

- Post pictures and videos of you traveling to desirable places.

- Put captions that subtly (this is crucial) imply you have it all figured out (keywords to remember: financial freedom, living life on your own terms, being your best self, etc.).

- Post everyday, multiple times per day, across as many platforms as you can. (Actually you should post 100 times. A day.)

And it’s not just children who have this desire of being known for the sake of being known, but full-grown adults. How else do you explain founder of Quest Nutrition, Tom Bilyeu, selling his company for $1 billion dollars, and then deciding to basically become a full-time YouTuber? It’s quite astounding, when you really stop and think about it, that individuals who amass hundreds of millions of dollars and essentially beat the game of life, when given the opportunity to do *anything,* make the same choice as 75% of people ages 6 to 17.

The rationalization here, of course, is that there is immeasurable value in “having an audience” and “being known on the Internet.”

You can do anything once you have an audience.

But to what end? And at what cost?

3) You Are The Product

So you want to change yourself from a human being to a product?

(Please read this ?sentence three times.)

In order for personal branding to work — that is to say, in order to get people’s attention for the sake of getting attention — we should look no further than the masters of attention grabbing.

Facebook’s own research has “repeatedly found that its photo-sharing app is harmful to a significant percentage of teenagers,” according to the Wall Street journal. “Thirty-two percent of teen girls said that when they felt bad about their bodies, Instagram made them feel worse.” Facebook also reportedly found that 14% of boys in the United States said Instagram made them feel worse about themselves.

Of course, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, these are just tools. Brilliantly engineered tools with a psychology of their own, but tools nonetheless. Social media doesn’t work if no one is on it (if a truck full of cigarettes is parked in the woods and no one is there to smoke them, do the cigarettes cause cancer?). So while Facebook and Instagram certainly have some questions to answer, we’d like to push the conversation one step further and ask a different question.

Who is creating the content the algorithms are ramming down people’s feeds?

Influencers.

Online personalities.

Characters.

“Personal brands.”

Teenage girls don’t feel bad about their bodies because of Instagram’s double-tap Like feature. They feel bad about their bodies because Instagram continuously shows them pictures of other girls who starve themselves, spend 3 hours doing their make-up, and then take a photo of themselves in perfect lightning with the caption, “Just being myself #authentic.” And teenage boys don’t feel bad about themselves because of Instagram’s square-by-square profile layout. Teenage boys feel bad about themselves because they see video after video of Dan Bilzerian jet-skiing with a gaggle of topless models with captions like, “Don’t get stuck in a cubicle.”

In the context of Facebook, Instagram, and other social media platforms that monetize your attention via ads, yes, you are the product.

But it’s also worth pointing out that in order to get your attention in the first place, there need to be personalities and characters (“influencers” and “personal brands”) for you to pay attention to — which means, to them, you are also the product.

What makes Dan Bilzerian, Dan Bilzerian, is that 32.6 million boys want to be like him.

This is an excerpt from Category Pirates Mini-eBook, “The “Me” Disease: Why Personal Branding Is A Lie” by Eddie Yoon, Nicolas Cole & Christopher Lochhead — a top 1% paid business (mini-book) newsletter on Category Design & Category Creation thinking.

Category Design Rising

Thank you!?☠️

In one short year you made Category Pirates:

- A top 0.5% paid Business Newsletter

- Produce eight #1 bestsellers on Amazon

- #4 on the Substack business chart

- Helped design the Mini Business Book category

We’re grateful to all who pirate with us ???☠️

Two New Category Pirates Business Books Hit #1 at the Same Time

“Category Design has emerged as the most powerful business skill on the planet,” said Category Pirates Co-Creator, Nicolas Cole. “Over the past 20 years, Category Creation has gone from being a little-known ‘positioning’ secret from advertising legends like David Ogilvy, Leo Burnett, Al Ries, Jack Trout, Gary Halbert, and more, to now becoming the single most in-demand skill among business leaders, Fortune 500 executives, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, marketers, and even the next generation of digital creators.”

Christopher Lochhead, Eddie Yoon, and Nicolas Cole—otherwise known as the Category Pirates—are thought leaders of Category Creation and Category Design thinking in the digital age.

What is Category Design?

On average, category leaders earn 76% of the total value created in their market and have market capitalizations that are five to eight times higher than comparable high-growth companies. As a result, successful Category Designers are the people who earn the vast majority of the economic value created in a given market—and are the ones best positioned to make an outsized difference in the world.

Given the global success of Harvard Business Review articles such as “Why It Pays to Be a Category Creator” and “Category Creation Is the Ultimate Growth Strategy” (authored by Category Pirate, Eddie Yoon) and the first book on Category Design, “Play Bigger: How Pirates, Dreamers, and Innovators Create and Dominate Markets” (Co-Authored by Category Pirate Christopher Lochhead), there has been a growing understanding in business that in order to have a meaningful impact, in order to “become known for a niche you own,” and in order to dominate an industry, you must create a new category for yourself (or redesign an existing one in your favor).

“The Category Design Toolkit”

In this book, people will learn:

- How to objectively measure whether you and your company are creating a new category versus competing in someone else’s (existing) category.

- How to prosecute The Magic Triangle: product design, company/business model design, and category design.

- The importance of being a missionary versus a mercenary—and why mercenary entrepreneurs and executives unknowingly compete over 24% of the market.

- How to find your Superconsumers, and leverage Superconsumer data to discover new potential categories.

- How to engineer a category breakthrough (even if you think your industry is “too saturated” or “all the good ideas are taken”).

- The 8 category differentiation levers, and all the ways you can create a defensible moat around your business.

- How you can apply category creation & category design principles even as a small “e” entrepreneur or local business owner.

- How category design can also be applied to your career (and why you should aim to become known for a niche you own, not “build a personal brand).

- What happens if you neglect your category—and how to rage category violence industry leaders who make this mistake.

- How to write a legendary S-1 and raise hundreds of millions (even billions) of dollars in your company’s IPO by making a case for the future growth of your category (which you created & designed).

- Why “Blue Ocean” isn’t what you are looking for. And if you want to truly create a category of your own, you should execute a No Ocean Strategy.

The Category Design Toolkit is everything people need to know in order to learn, practice, and master the skill of category design.

“A Marketer’s Guide To Category Design: How To Escape The ‘Better’ Trap, Dam The Demand, And Launch A Lightning Strike Strategy”

In A Marketer’s Guide To Category Design, people will learn:

- There is a new category of “human” in today’s world: Native Digitals (people under the age of 35 years old). And if you are a Native Analog, then all of your marketing efforts need to sit in this new context called, “For Native Digitals, the digital world is the real world.”

- Why so many marketers, entrepreneurs, executives, and even investors fall for The Big Brand Lie (falsely believing it’s the company’s “brand” customers care about).

- The “Better” Trap: why comparison marketing never works, and causes comparison-focused companies to fight over only 24% of the market.

- How to successfully execute a Dam The Demand strategy, stopping customers in the “old” world and moving them over to the new & different future you are creating.

- How to launch a Lightning Strike Strategy—and why “Peanut Butter Marketing” (spread out evenly throughout the year) is a guaranteed path to irrelevancy.

- What most marketers don’t understand about Black Friday, and why discount campaigns and coupons are a bad way to grow your business.

- And finally, the difference between content marketing that captures people’s attention and makes a difference versus content that goes nowhere.

About Category Pirates

Category Pirates is the leading authority on category design and category creation. We publish newsletters and books for the radically different—who want to see, design and claim the future.

Category Pirates’ newsletter is in the top 1% paid of paid newsletters on the Internet, and currently at charting at #7 in the subcategory of “business” on Substack. Category Pirates has published over 20 books with multiple books achieving #1 status on Amazon.com in multiple business, strategy, and marketing categories.

Eddie Yoon, Nicolas Cole and Christopher Lochhead are the Co-Creators of Category Pirates.

Contact:

Ca*************@***il.com

Podcast Magazine Names Follow Your Different “Best Business Podcast”

Podcast Magazine calls Christopher Lochhead | Follow Your Different™ the “Best Business Podcast”.

In their profile, “Christopher Lochhead: Following His ‘Different’ To Massive Success” they write:

“His candor, combined with a rare combination of wit and intelligence, offers listeners a refreshing voice”

Read the complete story here.

Languaging: The Strategic Use Of Language To Change Thinking

This is based on the Category Pirates ?☠️ Newsletter.

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and fellow Category Pirate,

Category Design is a game of thinking.

You are responsible for changing the way a reader, customer, consumer, or user “thinks.” And you are successful when you’ve moved their thinking from the old way to the new and different way you are educating them about.

The way you do this is with words.

Which means if you can’t write what you’re thinking, then you aren’t thinking clearly. And if you aren’t thinking clearly, then how are you going to change the way the reader, customer, consumer, or user thinks?

In previous letters, we have written about the different levers you can push and pull to differentiate your business (and even how to differentiate yourself in your career). But how you get customers to understand what makes you different, how you get investors to understand why you’re moving from one profit model to another (like Adobe did), and how you get employees, team members, and fellow executives to align their efforts (aka: align their *thinking*) is by using very specific, very intentional language. (At first blush, it’s hard to be against something called, “The Clean Air Act.” That’s on purpose.)

The strategic use of language to change thinking is called Languaging.

We believe this is one of the most under-discussed, unexamined aspects of business & marketing today.

- When President Biden orders U.S. immigration enforcement agencies to change how they talk about immigrants and change terms like “Illegal Alien” to “Undocumented Noncitizen,” that’s languaging.

- When the dairy industry spends 100 years educating the general public that milk comes from cows, and then someone comes along and introduces “Almond Milk” (or Oat Milk, or Flax Milk), that’s languaging.

- When the whole world understands what an acoustic guitar is, and Les Paul comes along and starts wailing away on an “Electric Guitar,” that’s languaging.

Languaging is about creating distinctions between old and new, same and different.

Legendary Category Designers are Languaging Masters.

A demarcation point in language creates a demarcation point in thinking, creates a demarcation point in action, creates a demarcation point in outcome.

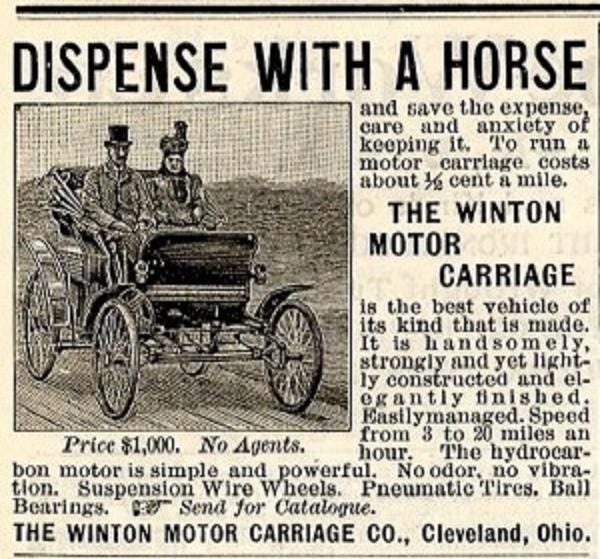

When Henry Ford called the first vehicle a “horseless carriage,” he was using language to get the customer to STOP, listen, and immediately understand the FROM-TO: the way the world was to the new and different way he wanted it to be. Had he called the first vehicle a “faster horse,” that would have been lazy languaging (and lazy thinking).

Sara Blakely insisted that Spanx was not just a “product,” it was an “invention.” Today Britannica lists her as an “American Inventor.” That’s not an accident. It’s the strategic use of language.

And it all starts with your POV.

Your Point Of View Of The Category Is What “Hooks” The Customer

The language you use reflects your Point Of View.

And your Point Of View frames a new problem and a new solution in a provocative way.

If marketing is your ability to evangelize a new category, and branding is how well you can associate your product with the benefits of the category, then languaging is how you market the category, and your brand within that category, based on your company’s unwavering, unquestionably unique point of view.

You can tell when a company doesn’t have a unique POV of their category when their “messages” conflict with one another, have unclarified and “weak” aims, or worst of all, have no clear aim at all. Today they’re evangelizing one category, tomorrow they’re evangelizing a different category (all the while thinking they are “trying out different marketing & messaging phrases”).

For example, a cereal company might run one advertisement saying, “The healthiest way to start the day!” The very next campaign, however, they might change the message to, “A healthy breakfast alternative.” What’s the cereal company’s unwavering POV of the category?

Is it that breakfast is the best way to start the day—and they’re the solution?

Or is it that breakfast isn’t the best way to start the day—and they’re the solution?

Frame it, Name it, and Claim it

Companies with unclarified, undefined POVs eventually come to the conclusion that they have a problem (sales are down). But they end up stating the root of their problem in the way they ask for help: “We need to work on our messaging.” More times than not, what they mean when they say “messaging” isn’t actually messaging—but category point of view.

As a side note, most messaging is meaningless, context free, point of view-less, forgettable garbage. “Experience amazing,” “Imagination at work,” “That’s what I like,” “Run simple,” are taglines for who? Don’t know? Neither does anyone else. Lexus. GE. Pepsi. SAP.

The reason this clarity is so important, and why we want to draw lines in the sand between category point of view, languaging, and messaging, is because improving a company’s messaging in absence of a true north category POV is a (and we use this word very intentionally) “meaningless,” money burning project.

- A POV is, “What do we stand for?”

- Languaging is, “How do we powerfully communicate our POV?”

- And messaging is, “What should we say?”

Well, how can you possibly know what to say unless you know what you stand for? What difference do you make in the world? What problem do you solve?

Your point of view should be well defined and chiseled into the company’s tablets, with intentionally chosen words that reflect the company’s POV, so the true science of messaging can begin: a never-ending experiment of swapping in and out of words, phrases, promotions, testimonials, and other “messages” in order to figure out which are (another very intention word here) resonating and most effectively evangelizing your category POV.

And it all starts with how you choose to Frame, Name, and Claim the problem.

For example, there’s a reason why men have “erectile dysfunction” and not “impotence.”

Impotence has very negative implications attached to the word. If a man says he is impotent, it’s as though he has a character flaw. It means “not manly” or “unable to be a man.” That’s not a word very many men want to be associated with—meaning men don’t want to admit to having such a problem. (Hard to sell a solution to a problem no one wants to admit to having!)

In order to solve this problem, Pfizer (the makers of Viagra) had to invent a disease, called “erectile dysfunction,” to make impotence a more approachable problem. And then they shortened it to “ED” to make it even softer and safer to associate with. It’s a whole lot easier for a man to say, “I am experiencing ED” than to say “I am impotent.”

This is what languaging does.

It changes the way people perceive the thing they’re looking at.

Netflix is another legendary example.

Their POV is that you should be able to watch anything you want, whenever you want. That’s the “frame” of the problem. They then Name & Claim the solution to that problem: “streaming.”

But what Netflix also did was also Frame, Name, and Claim the OLD category experience too. And they did so in a way that was functionally accurate and simultaneously spelled out the problem immediately for customers. They called it “appointment viewing.”

In order for “streaming” and on-demand to work, you also have to believe “appointment viewing” is a problem. And nobody in the ‘90s and 2000s thought “appointment viewing” was a problem. You just assumed you could only watch what you wanted to watch at the hour it was on. As a result, the language people used back then when asking their friends and family about a new TV show was, “When is it on?”

This phrase, this language, no longer exists.

Today, we don’t ask, “When is it on?” The new category overtook the old category—which means new language replaces the old language. Now we ask, “What is it on? Netflix? Disney+? Peacock? Hulu?”

Whoever Names & Frames the problem Claims the language—and wins.

It’s the POV and the language you use to reflect that POV that makes your “messaging” inspire customers to take action — not the other way around.

In your marketing, branding, product descriptions, etc., language has the potential to reflect the unspoken qualities of your category point of view. Our good friend Lee Hartley Carter, communication expert and author of Persuasion: Convincing Others When Facts Don’t Seem To Matter, refers to this as “the understanding that language has the power to create thinking, which in turn inspires action.”

For example, when you walk into a coffee shop, any coffee shop other than Starbucks, what words do coffee drinkers frequently use to order their coffee? “Hi, I’d like a double grande latte please.” But “Grande” isn’t the universal word for “medium.” It’s Starbucks’ word, which a good chunk of the category has adopted. You can’t name a new, different thing, the same as the old thing. Starbucks would never have succeeded unless they designed their own category lexicon. No one would pay $4.00 for a coffee. But they do it for a “Grande.”

Another genius of Starbucks category languaging is that their words are new, fresh, and yet familiar at the same time. The first time we hear, “Venti Mocha,” we have an idea what that might mean. Even though we had never heard it before.

Category queens deliberately use languaging to do a few things:

- To differentiate themselves from any and all competition through word choice, tone, and nuance.

- To speak to (and speak “like”) the customers they want to attract—especially the Superconsumers of the category.

- To further establish their position in the category they are designing or redesigning.

- To insinuate and give context to the rest of the 8 levers: price, profit model, branding, etc., and how the company executes any number of them in a different way.

Languaging can be applied to all 8 levers of category differentiation:

If you want to put your company’s POV to the test, walk through the 8 levers and question how intentionally you are using language to educate customers on the differences between the new category you are creating and the old category that currently exists.

Languaging helps you name the category you are creating (by framing a different problem with a different benefit): There are cars, and then there are electric cars. There’s digital marketing, and then there is chatbot marketing.

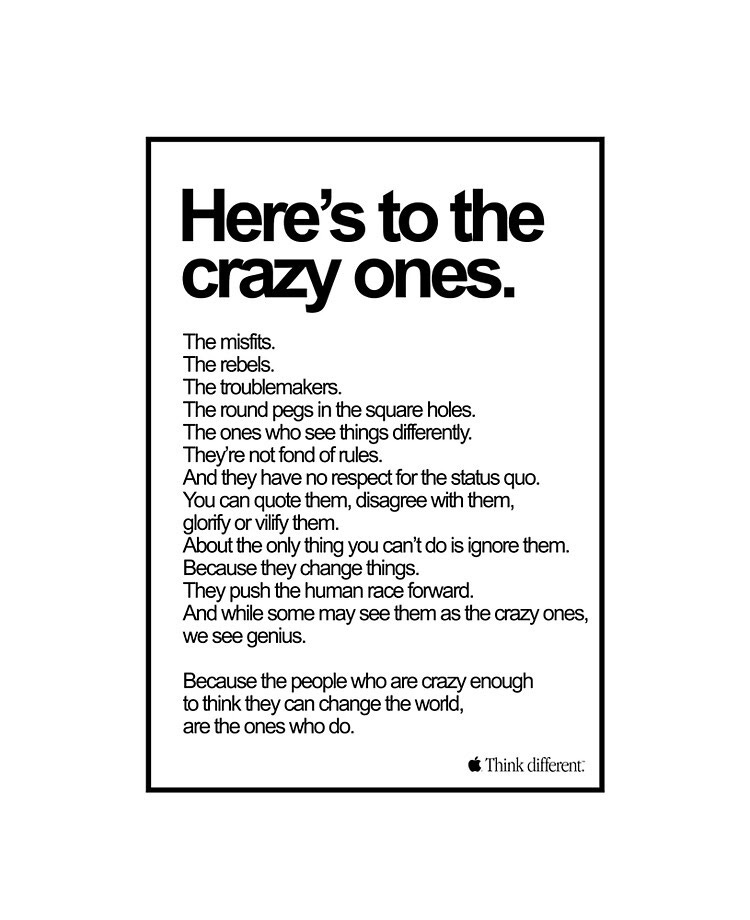

Languaging is how you write a compelling mission statement for your brand: Apple’s “Think Different” is a great example (which works because the proper way to say that is, of course, “Think Differently. Apple changing the word to the grammatically incorrect “different” forces the reader to stop.) Same with “Here’s to the crazy ones.” These are some of the best examples of intentional language that ties the audience of the new category and the mission statement of the brand together.

Languaging educates the customer on the experience you are proposing: Streaming video implies a very different experience than getting in your car, driving to your local Blockbuster, and renting a video. Same goes for today’s contactless pick-up at grocery stores and restaurants versus standard “pick up” practices.

Languaging frames the perceived value of your product or service: A medium coffee is perceived to be cheap, but a Grande coffee is perceived to be expensive.

Languaging hints at the benefits that come with radically different manufacturing: An e-book is a dematerialized book. It can be produced infinitely, distributed infinitely, edited and uploaded in an instant, etc.

Languaging also hints at the benefits that come with radically different distribution: OnlyFans calling creators you invite to the platform using your referral link “Referred Creators” signals the benefits of their flywheel and the money you can earn as a result.

Languaging is the “hook” customers, consumers, and users latch onto in your marketing: Substack’s paid newsletters are a different thing than Mailchimp’s free newsletters. Marketing something fundamentally different is always easier and more enticing to the customer than trying to market something that is “better” than what currently exists, but still the same kind of thing.

Languaging also signals to customers how to think about paying for your product or service: Paying a subscription is different than buying products individually. Or purchasing in-game items inside a free video game is different than playing a freemium game with ads. (These are all words and phrases that did not exist until recently, and were purposely used to design new categories.)

Too many marketers, executives, founders, and even venture capital firms think the words a company uses are all about “standing out.”

But you can’t stand out without a clear and different POV. Lexus can scream “Experience Amazing” all it wants and most people will never be able to recall those words and connect them to their brand. Because they do not frame a problem.

You can’t stand out if your POV isn’t being communicated through intentional languaging.

In fact, “languaging” is often more about who the brand, product, and company is NOT for than who the brand is for. The more directly you can speak to the people you are trying to help most, the more likely it is for them to see you as the “undeniable champion” solution of the category you are creating. But the moment you try to widen your net (purely for the sake of “going after a bigger audience”), you begin to dilute your language. Your words become generalized and vague. You aren’t speaking to any “one” person. And if you keep going, and widen your company’s language to be “something for everything,” all of your messaging ends up being another frequency wave in the never-ending hum of white noise—something for no one. (SAP’s message is meaningingful to no one: “Run Simple.”)

When languaging is executed successfully, and is reflective of a well-defined POV of the category, two things happen.

1. You become known for the new language you’ve invented.

You know your languaging is working when customers start using the language you created.

For example, in the early 2000s, Salesforce founder, Marc Benioff created new language for the new category he was creating. He called it “cloud-based software.” (There’s “software” you buy and install on your computer via CD-ROM, and there’s “cloud-based software” you buy and use from any computer, and any browser connected to the Internet.)

In addition, and to further “twist the knife” into the backs of his competitors, he also invented language to reframe the way people thought about the old category by referring to it as “on-premise software.” Notice the distinction: “On-premise software” runs on computers on the premises of the person or organization using the software. “Cloud-based software” runs on a remote facility outside the organization.

What happened?

The entire technology industry started adopting the language he and Salesforce invented.

2. Customers don’t see you as “better.” They see you as different.

The second thing that happens when you successfully use language to change thinking is you dam the demand.

When you use intentional language to modify the existing category (“cloud-based software”), you create a chasm between the old and the new. For example, an “e-bike” is not better than a “bicycle.” It’s something different. It has different benefits, different use cases, even different price points, profit models, and manufacturing processes. One single letter and a dash tells the reader/customer/consumer/user “this thing is not like what came before it.” Same goes for “frozen food” and “fresh food,” or “sunglasses” and “glasses.” These languaging modifications make the customer STOP, tilt their head, and immediately wonder, “This is for something different—do I need this?”

And since you were the one who invented the language, you become the trusted authority to educate them on the definition of that new language—and subsequently, that new category.

Languaging is how you change the world.

At the highest level, languaging is used to move society forward.

Not long ago, people living on the streets were called “whinos” and “bumbs.” Today, they are called, “people experiencing homelessness.” This new languaging changes how people perceive the problem and subsequently treat others and work toward a solution.

Remember: A demarcation point in language creates a demarcation point in thinking, creates a demarcation point in action, creates a demarcation point in outcome.

There was also a point in time when the minimum wage for women was lower than it was for men. Women got paid less. Until a movement mobilized around some strategic, future-changing languaging: “Equal pay for equal work.” These words were so powerful, they changed the law.

And sometimes, languaging emerges through new combinations of words into a portmanteau.

- Gamification

- Infotainment

- Brunch

- Podcast

- Frenemy

Whenever language is bent, it tweaks the ear to listen—and to consider the different.

We all have AIDS.

In 2005, fashion designer, Kenneth Cole, launched an AIDS awareness campaign in conjunction with the American Foundation for AIDS Research. The POV was: “We All Have AIDS… If One Of Us Does.”

Notice, this is not “a clever message.” This is a radically different, crystal clear point of view of the world, reflected through languaging: the strategic use of language to change thinking.