Languaging: The Strategic Use Of Language To Change Thinking

This is based on the Category Pirates ?☠️ Newsletter.

Dear Friend, Subscriber, and fellow Category Pirate,

Category Design is a game of thinking.

You are responsible for changing the way a reader, customer, consumer, or user “thinks.” And you are successful when you’ve moved their thinking from the old way to the new and different way you are educating them about.

The way you do this is with words.

Which means if you can’t write what you’re thinking, then you aren’t thinking clearly. And if you aren’t thinking clearly, then how are you going to change the way the reader, customer, consumer, or user thinks?

In previous letters, we have written about the different levers you can push and pull to differentiate your business (and even how to differentiate yourself in your career). But how you get customers to understand what makes you different, how you get investors to understand why you’re moving from one profit model to another (like Adobe did), and how you get employees, team members, and fellow executives to align their efforts (aka: align their *thinking*) is by using very specific, very intentional language. (At first blush, it’s hard to be against something called, “The Clean Air Act.” That’s on purpose.)

The strategic use of language to change thinking is called Languaging.

We believe this is one of the most under-discussed, unexamined aspects of business & marketing today.

- When President Biden orders U.S. immigration enforcement agencies to change how they talk about immigrants and change terms like “Illegal Alien” to “Undocumented Noncitizen,” that’s languaging.

- When the dairy industry spends 100 years educating the general public that milk comes from cows, and then someone comes along and introduces “Almond Milk” (or Oat Milk, or Flax Milk), that’s languaging.

- When the whole world understands what an acoustic guitar is, and Les Paul comes along and starts wailing away on an “Electric Guitar,” that’s languaging.

Languaging is about creating distinctions between old and new, same and different.

Legendary Category Designers are Languaging Masters.

A demarcation point in language creates a demarcation point in thinking, creates a demarcation point in action, creates a demarcation point in outcome.

When Henry Ford called the first vehicle a “horseless carriage,” he was using language to get the customer to STOP, listen, and immediately understand the FROM-TO: the way the world was to the new and different way he wanted it to be. Had he called the first vehicle a “faster horse,” that would have been lazy languaging (and lazy thinking).

Sara Blakely insisted that Spanx was not just a “product,” it was an “invention.” Today Britannica lists her as an “American Inventor.” That’s not an accident. It’s the strategic use of language.

And it all starts with your POV.

Your Point Of View Of The Category Is What “Hooks” The Customer

The language you use reflects your Point Of View.

And your Point Of View frames a new problem and a new solution in a provocative way.

If marketing is your ability to evangelize a new category, and branding is how well you can associate your product with the benefits of the category, then languaging is how you market the category, and your brand within that category, based on your company’s unwavering, unquestionably unique point of view.

You can tell when a company doesn’t have a unique POV of their category when their “messages” conflict with one another, have unclarified and “weak” aims, or worst of all, have no clear aim at all. Today they’re evangelizing one category, tomorrow they’re evangelizing a different category (all the while thinking they are “trying out different marketing & messaging phrases”).

For example, a cereal company might run one advertisement saying, “The healthiest way to start the day!” The very next campaign, however, they might change the message to, “A healthy breakfast alternative.” What’s the cereal company’s unwavering POV of the category?

Is it that breakfast is the best way to start the day—and they’re the solution?

Or is it that breakfast isn’t the best way to start the day—and they’re the solution?

Frame it, Name it, and Claim it

Companies with unclarified, undefined POVs eventually come to the conclusion that they have a problem (sales are down). But they end up stating the root of their problem in the way they ask for help: “We need to work on our messaging.” More times than not, what they mean when they say “messaging” isn’t actually messaging—but category point of view.

As a side note, most messaging is meaningless, context free, point of view-less, forgettable garbage. “Experience amazing,” “Imagination at work,” “That’s what I like,” “Run simple,” are taglines for who? Don’t know? Neither does anyone else. Lexus. GE. Pepsi. SAP.

The reason this clarity is so important, and why we want to draw lines in the sand between category point of view, languaging, and messaging, is because improving a company’s messaging in absence of a true north category POV is a (and we use this word very intentionally) “meaningless,” money burning project.

- A POV is, “What do we stand for?”

- Languaging is, “How do we powerfully communicate our POV?”

- And messaging is, “What should we say?”

Well, how can you possibly know what to say unless you know what you stand for? What difference do you make in the world? What problem do you solve?

Your point of view should be well defined and chiseled into the company’s tablets, with intentionally chosen words that reflect the company’s POV, so the true science of messaging can begin: a never-ending experiment of swapping in and out of words, phrases, promotions, testimonials, and other “messages” in order to figure out which are (another very intention word here) resonating and most effectively evangelizing your category POV.

And it all starts with how you choose to Frame, Name, and Claim the problem.

For example, there’s a reason why men have “erectile dysfunction” and not “impotence.”

Impotence has very negative implications attached to the word. If a man says he is impotent, it’s as though he has a character flaw. It means “not manly” or “unable to be a man.” That’s not a word very many men want to be associated with—meaning men don’t want to admit to having such a problem. (Hard to sell a solution to a problem no one wants to admit to having!)

In order to solve this problem, Pfizer (the makers of Viagra) had to invent a disease, called “erectile dysfunction,” to make impotence a more approachable problem. And then they shortened it to “ED” to make it even softer and safer to associate with. It’s a whole lot easier for a man to say, “I am experiencing ED” than to say “I am impotent.”

This is what languaging does.

It changes the way people perceive the thing they’re looking at.

Netflix is another legendary example.

Their POV is that you should be able to watch anything you want, whenever you want. That’s the “frame” of the problem. They then Name & Claim the solution to that problem: “streaming.”

But what Netflix also did was also Frame, Name, and Claim the OLD category experience too. And they did so in a way that was functionally accurate and simultaneously spelled out the problem immediately for customers. They called it “appointment viewing.”

In order for “streaming” and on-demand to work, you also have to believe “appointment viewing” is a problem. And nobody in the ‘90s and 2000s thought “appointment viewing” was a problem. You just assumed you could only watch what you wanted to watch at the hour it was on. As a result, the language people used back then when asking their friends and family about a new TV show was, “When is it on?”

This phrase, this language, no longer exists.

Today, we don’t ask, “When is it on?” The new category overtook the old category—which means new language replaces the old language. Now we ask, “What is it on? Netflix? Disney+? Peacock? Hulu?”

Whoever Names & Frames the problem Claims the language—and wins.

It’s the POV and the language you use to reflect that POV that makes your “messaging” inspire customers to take action — not the other way around.

In your marketing, branding, product descriptions, etc., language has the potential to reflect the unspoken qualities of your category point of view. Our good friend Lee Hartley Carter, communication expert and author of Persuasion: Convincing Others When Facts Don’t Seem To Matter, refers to this as “the understanding that language has the power to create thinking, which in turn inspires action.”

For example, when you walk into a coffee shop, any coffee shop other than Starbucks, what words do coffee drinkers frequently use to order their coffee? “Hi, I’d like a double grande latte please.” But “Grande” isn’t the universal word for “medium.” It’s Starbucks’ word, which a good chunk of the category has adopted. You can’t name a new, different thing, the same as the old thing. Starbucks would never have succeeded unless they designed their own category lexicon. No one would pay $4.00 for a coffee. But they do it for a “Grande.”

Another genius of Starbucks category languaging is that their words are new, fresh, and yet familiar at the same time. The first time we hear, “Venti Mocha,” we have an idea what that might mean. Even though we had never heard it before.

Category queens deliberately use languaging to do a few things:

- To differentiate themselves from any and all competition through word choice, tone, and nuance.

- To speak to (and speak “like”) the customers they want to attract—especially the Superconsumers of the category.

- To further establish their position in the category they are designing or redesigning.

- To insinuate and give context to the rest of the 8 levers: price, profit model, branding, etc., and how the company executes any number of them in a different way.

Languaging can be applied to all 8 levers of category differentiation:

If you want to put your company’s POV to the test, walk through the 8 levers and question how intentionally you are using language to educate customers on the differences between the new category you are creating and the old category that currently exists.

Languaging helps you name the category you are creating (by framing a different problem with a different benefit): There are cars, and then there are electric cars. There’s digital marketing, and then there is chatbot marketing.

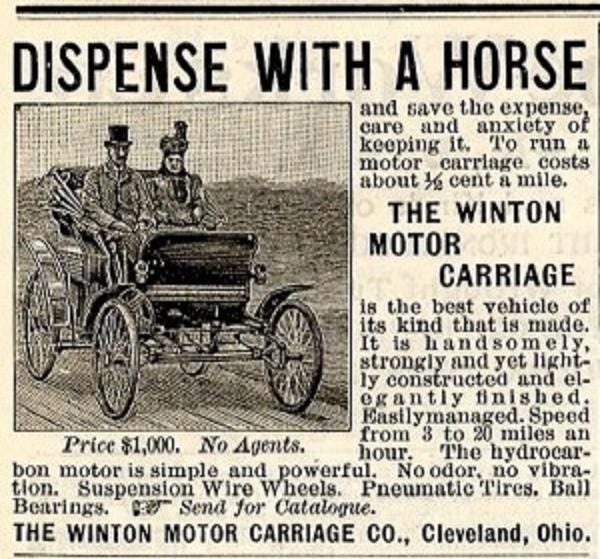

Languaging is how you write a compelling mission statement for your brand: Apple’s “Think Different” is a great example (which works because the proper way to say that is, of course, “Think Differently. Apple changing the word to the grammatically incorrect “different” forces the reader to stop.) Same with “Here’s to the crazy ones.” These are some of the best examples of intentional language that ties the audience of the new category and the mission statement of the brand together.

Languaging educates the customer on the experience you are proposing: Streaming video implies a very different experience than getting in your car, driving to your local Blockbuster, and renting a video. Same goes for today’s contactless pick-up at grocery stores and restaurants versus standard “pick up” practices.

Languaging frames the perceived value of your product or service: A medium coffee is perceived to be cheap, but a Grande coffee is perceived to be expensive.

Languaging hints at the benefits that come with radically different manufacturing: An e-book is a dematerialized book. It can be produced infinitely, distributed infinitely, edited and uploaded in an instant, etc.

Languaging also hints at the benefits that come with radically different distribution: OnlyFans calling creators you invite to the platform using your referral link “Referred Creators” signals the benefits of their flywheel and the money you can earn as a result.

Languaging is the “hook” customers, consumers, and users latch onto in your marketing: Substack’s paid newsletters are a different thing than Mailchimp’s free newsletters. Marketing something fundamentally different is always easier and more enticing to the customer than trying to market something that is “better” than what currently exists, but still the same kind of thing.

Languaging also signals to customers how to think about paying for your product or service: Paying a subscription is different than buying products individually. Or purchasing in-game items inside a free video game is different than playing a freemium game with ads. (These are all words and phrases that did not exist until recently, and were purposely used to design new categories.)

Too many marketers, executives, founders, and even venture capital firms think the words a company uses are all about “standing out.”

But you can’t stand out without a clear and different POV. Lexus can scream “Experience Amazing” all it wants and most people will never be able to recall those words and connect them to their brand. Because they do not frame a problem.

You can’t stand out if your POV isn’t being communicated through intentional languaging.

In fact, “languaging” is often more about who the brand, product, and company is NOT for than who the brand is for. The more directly you can speak to the people you are trying to help most, the more likely it is for them to see you as the “undeniable champion” solution of the category you are creating. But the moment you try to widen your net (purely for the sake of “going after a bigger audience”), you begin to dilute your language. Your words become generalized and vague. You aren’t speaking to any “one” person. And if you keep going, and widen your company’s language to be “something for everything,” all of your messaging ends up being another frequency wave in the never-ending hum of white noise—something for no one. (SAP’s message is meaningingful to no one: “Run Simple.”)

When languaging is executed successfully, and is reflective of a well-defined POV of the category, two things happen.

1. You become known for the new language you’ve invented.

You know your languaging is working when customers start using the language you created.

For example, in the early 2000s, Salesforce founder, Marc Benioff created new language for the new category he was creating. He called it “cloud-based software.” (There’s “software” you buy and install on your computer via CD-ROM, and there’s “cloud-based software” you buy and use from any computer, and any browser connected to the Internet.)

In addition, and to further “twist the knife” into the backs of his competitors, he also invented language to reframe the way people thought about the old category by referring to it as “on-premise software.” Notice the distinction: “On-premise software” runs on computers on the premises of the person or organization using the software. “Cloud-based software” runs on a remote facility outside the organization.

What happened?

The entire technology industry started adopting the language he and Salesforce invented.

2. Customers don’t see you as “better.” They see you as different.

The second thing that happens when you successfully use language to change thinking is you dam the demand.

When you use intentional language to modify the existing category (“cloud-based software”), you create a chasm between the old and the new. For example, an “e-bike” is not better than a “bicycle.” It’s something different. It has different benefits, different use cases, even different price points, profit models, and manufacturing processes. One single letter and a dash tells the reader/customer/consumer/user “this thing is not like what came before it.” Same goes for “frozen food” and “fresh food,” or “sunglasses” and “glasses.” These languaging modifications make the customer STOP, tilt their head, and immediately wonder, “This is for something different—do I need this?”

And since you were the one who invented the language, you become the trusted authority to educate them on the definition of that new language—and subsequently, that new category.

Languaging is how you change the world.

At the highest level, languaging is used to move society forward.

Not long ago, people living on the streets were called “whinos” and “bumbs.” Today, they are called, “people experiencing homelessness.” This new languaging changes how people perceive the problem and subsequently treat others and work toward a solution.

Remember: A demarcation point in language creates a demarcation point in thinking, creates a demarcation point in action, creates a demarcation point in outcome.

There was also a point in time when the minimum wage for women was lower than it was for men. Women got paid less. Until a movement mobilized around some strategic, future-changing languaging: “Equal pay for equal work.” These words were so powerful, they changed the law.

And sometimes, languaging emerges through new combinations of words into a portmanteau.

- Gamification

- Infotainment

- Brunch

- Podcast

- Frenemy

Whenever language is bent, it tweaks the ear to listen—and to consider the different.

We all have AIDS.

In 2005, fashion designer, Kenneth Cole, launched an AIDS awareness campaign in conjunction with the American Foundation for AIDS Research. The POV was: “We All Have AIDS… If One Of Us Does.”

Notice, this is not “a clever message.” This is a radically different, crystal clear point of view of the world, reflected through languaging: the strategic use of language to change thinking.

The campaign then featured figures such as former South African President Nelson Mandela, South African advocate Zackie Achmat, South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, as well as actresses Ashley Judd, Sharon Stone, and Elizabeth Taylor, and actors such as Tom Hanks, Will Smith, and so on, all with the chief aim of minimizing the stigma associated with the disease. Kenneth Cole & the American Foundation for AIDS Research wanted to dispel the myth that AIDS is only an issue for HIV-positive people.

How?

By saying, very clearly, “If anyone is infected, we are all affected. If it exists anywhere, it exists everywhere.”

Languaging + Math = Story Arc.

One last thing.

If languaging is how you communicate your differentiated POV, then numbers are how you communicate the urgency of your POV.

Numbers are what give your story an arc.

In everything you say, you are either communicating one of two story arcs. Either you have no treasure, and you’ve found a map that says there’s lots of treasure over there. Or, you’re Chicken Little with lots of treasure warning everyone the sky is falling. Numbers are the evidence, and amplify the language.

To be clear, we’re not saying you need to understand how to perform statistical analyses or do napkin calculus. (Pirate Christopher failed 3rd-grade math, and Pirate Cole still counts with his fingers.) Languaging masters simply need to understand whether something small today could be gargantuan tomorrow, or something big today could be small, even nonexistent tomorrow—and then strategically use language to educate readers, listeners, customers, and consumers on the importance of that story arc.

The Origin Story of McKinsey

For example, McKinsey & Company was a firm founded in 1926 by James O. McKinsey, a University of Chicago accounting professor. McKinsey started out as a group of bean counters and accountants, not the defacto standard of world-class professional services we associate today with McKinsey.

Who built McKinsey into the powerhouse firm it became was Marvin Bower, the Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School graduate hired by James O. McKinsey. Bower had a powerful a-ha. He discovered a “missing.” He noticed that while clients paid for accounting services, what they often valued more was business advice from a trusted source.

Mavin Bower is the category designer of management consulting.

He was a languaging maniac.

Under his guide, projects were not called “jobs.” They were engagements—a word that is much more relational than transactional. Internal groups with specific industry or functional expertise were called practices (Like doctors, this is the intentional use of language to create the perception of value)—emphasizing that learning was a never-ending endeavor. Finally, McKinsey was not a “business.” It was a firm—highlighting the core values that held the company together. Even today there are few firms who are as rigorously committed (some might say cultishly committed) to the original language Marvin Bower put into place.

All of these distinctions helped McKinsey thrive and create the $255 billion dollar global category known today as Management Consulting. And notice history remembers the lawyer, Marvin Bower (lawyers are trained in the discipline of language), not the accountant, as the “father of management consulting.”

All legendary languaging represents 1 of 4 math equations:

- Addition

- Subtraction

- Multiplication

- Division

If your languaging does not tell one of these 4 story arcs, no one is going to listen to what you have to say. There is no urgency. You are responsible not just for strategically using new words to frame new problems (or reframe old problems), but also reveal whether the slope is positive or negative—are the numbers going up or down? Where is this story going? And your ability to comprehend and communicate that slope is what makes your languaging matter.

- Addition: “With C4 pre-workout, your workouts will last longer.”

- Subtraction: “With Spanx, pounds seemingly disappear. A flat stomach in seconds.”

- Multiplication: “With an acoustic guitar, only some people can hear your music. With an electric guitar, an entire stadium of people can hear your music.”

- Division: “Condoms are 98% effective at protecting against and reducing the spread of most STDs.”

The power of language can be multiplied (pun intended) when paired with numbers to create new langauging.

Numbers tell powerful stories too.

So as you sail forward in life and business, we ask that you pay special attention to the Framing, Naming, and Claiming of things. Because we get taught to think by the words people use with us (which means you can teach others to think by the words you use with them).

A demarcation point in language creates a demarcation point in thinking, creates a demarcation point in action, creates a demarcation point in outcome.

Arrrrrrr,

Category Pirates